Every flat surface inside the non-descript building in Brisbane, California, is covered in framed patents, records, art, posters with mottos … and in every room, photos of Noel Lee. The 66-year-old Lee is CEO (or as they affectionately refer to him, the Head Monster), and his joyful, wide grin appears in photos with all of your favorite artists. Turn a corner and you might see Lee in a Red Sox jersey with David Ortiz, or Lee up late, with Slash leaning on him after a night of partying too hard.

Lee’s personal office is lavish to say the least, but it feels lived in too, like anyone else’s desk might. Granted, there’s a table from the World Poker Tour, and a pinball machine, and an aquarium built into the wall. But these feel more like personally treasured objects than trophies of business conquest.

Monster is no ordinary business.

It’s not the corporate headquarters you might expect from a business that brings in over 100 million dollars a year, but Monster is no ordinary business. Love them or hate them — and let’s be clear, this company and this man inspire passion on both sides of the argument — you’ve got to respect the largest headphone manufacturer in the world.

But things weren’t always contentious. And like so many great California tech stories, the whole adventure started with just Lee and his son in the garage.

Back in the day

“Retailers needed opportunities to make money on TVs, to raise their profit margins,” Lee told Digital Trends. “Quality retailers had quality salespeople to sell to the product, then it was about enhancing the devices that people were buying.”

What most people forget about Monster is that it wasn’t always about gold-plated HDMI cables and colorful, over-ear headphones. Back in 1978 it was just Noel Lee, a touring drummer and audiophile, winding cables in his garage. It was a passion project for Lee, who describes himself then as a pocket-protector carrying engineer.

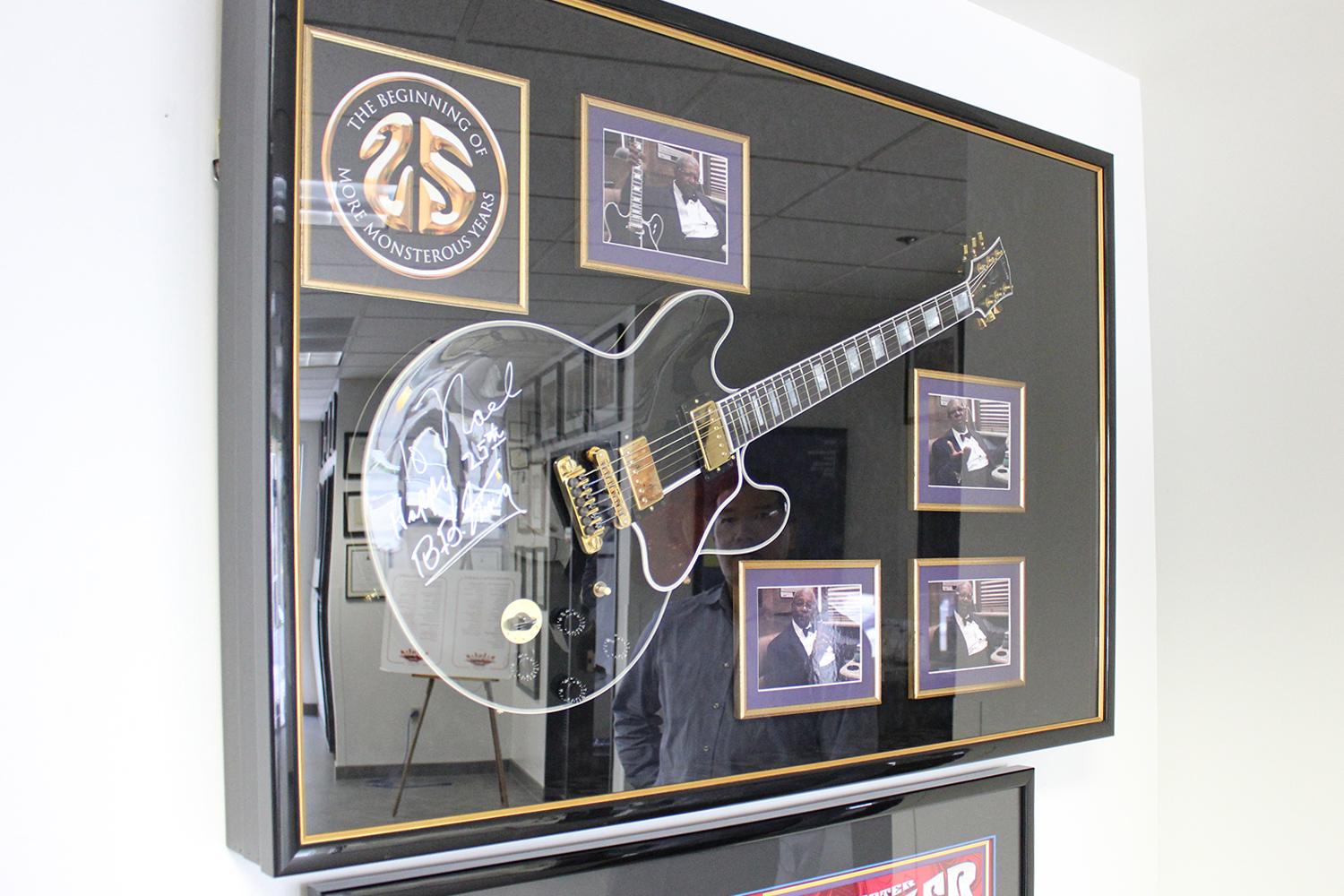

In some ways he’s still that guy, riding into his office, lined with model cars and extravagant gifts from famous musicians, on a golden Segway. The pocket protector is gone now, replaced by the well-tailored suit of a seasoned veteran of California business elite. Lee was immediately warm and friendly as he sat down with us, shuffling the box and instructions for an ice machine he’s assembling off his desk. Before we get to the serious stuff, it’s important to know the story of Monster in his words.

Monster built a business training salespeople to anticipate needs and suggest products to fill the customer’s basket. If they bought an amplifier, make sure they buy the right cable to go with it, Lee says, or the best surge protector. One of the main ways the company did this was to demo different cables right next to each other in the store, and get potential customers to hear a difference. It was a winning situation for stores, too.

“Really, when you listen on those white earbuds it’s like you’ve never heard your music.”

As a touring drummer for the country cover band Asian Wood, Lee is intimately familiar with demanding gear perfection. Nowadays, for Lee at least, running Monster is still about convincing people that their relationship with music could be more fulfilling. “We saw everyone using these white earbuds, and really when you listen on those it’s like you’ve never heard your music. When we partnered with Beats, they marketed the headphones, and we designed them. It was about creating deep bass for EDM, and the 808 hip-hop punch that kids hear in the club.”

“They’re also designed for showing off a bit, which is part of the appeal,” he admitted.

The split from Beats wasn’t exactly clean, but Lee still talks about it as another business decision. Whether that’s optimism or business acumen is hard to say, but even if it ended poorly, Monster learned a lot from their relationship with Ive and Dre. Beats was a big part of Monster’s move from audio cables to headphones and speakers, and set the company on a path to where it is now.

So why all the hate?

For an audio equipment company, Monster has attracted a lot more negative press than you would expect, certainly far more than any of its competitors. There are a few reasons for that, and where you place the blame likely correlates directly with your opinion of the brand.

The first issue is simply one of pricing. Monster cables are designed to have a high markup, that’s just part of the business model — creating a high profit margin product where there was none before. The problem is that outside of a huge equipment purchase, those high prices can look a little ridiculous. That’s only compounded by the fact that audio and videophiles are still conflicted as to whether a $24.95, gold-plated cable holds any real advantage over something you might get out of a bin at Fry’s for $3.99.

The other issue is that Monster Audio is a bit overprotective of its brand identity. It makes some amount of sense, with a number of other companies using the Monster name to promote everything from job search websites to energy drinks. That includes suing Disney over Monsters, Inc., the Boston Red Sox organization over the green monster, and an Oregon used clothing store called MonsterVintage.

In one of the more famous legal spats, Monster Audio sued a Rhode Island couple who were attempting to start “Monster Mini-Golf” in their own town. After the couple devoted months of work and over $100,000 in legal fees, Monster Audio finally relented and agreed to pay the couple’s court fees, but not before receiving hundreds of angry customer complaints.

Times are changing

There are a number of different philosophies that drive innovation at Monster today. Part of the equation is giving people what they want — finding out what that is and making it. The other part is deciding which markets to expand into, and in that area, not much has changed since 1978.

“We’re coming out of nowhere to compete with Sonos. They created the category, but we’re going to take them head-on. They innovated in control, connectivity, and audio, but we’re going to create a bigger market.”

“Musicians know they can call Noel up and talk shop. We don’t pay them for it. Drake wears our stuff, Snoop loves our stuff.”

Monster is still very much focused on disrupting existing platforms. Even when a brand has a huge lead in a market, that doesn’t stop Monster from jumping into the fray. Part of the equation is agility, too, which is why the word wireless doesn’t scare Lee.

“It could be Monster Wireless, you’ve gotta connect, that’s just the technology. We did really well with cable technology, that’s not to say we can’t do well with other technologies too.”

But Lee knows that his power as a connectivity company is limited, and that’s why they make sure it isn’t all about them.

“We can’t grow the company any bigger than us, but there are a lot of people with a bigger reach than us we want to build an affinity with. We’re open to working with companies, with manufacturers, with technologies. It’s about finding expertise in other areas and opening it up.”

Reaching out and making friends

While some companies might shoehorn celebrities into their business model in search of some good press, Monster pursues influencers who actually want to use their products, and brands that actually want to work with them.

“We partner with companies that don’t usually work with anyone, like Chanel. We’re looking to show our leadership in fashion, and there is no higher brand. We approached them with a headphone design, because headphones are part of a complete lifestyle brand.”

It’s all part of a larger plan to ensure that Monster stays relevant in an increasingly wireless world.

“It’s easy to have a conversation with Chanel to make a headphone, or watch brands, or car brands. If they already have a mind to extend their lifestyle brand with watches or fragrances, we’re the ones for the headphones.”

And the musicians and celebrities that have come on board? Lee says it’s because they love the products.

“Engaging with musicians … we’re music lovers, and musicians, and we relate to them. When we talk to a musician on their terms, they share an affinity. We’re not pay for play; if you love our product we want you to be an evangelist. They all like us because we’re the real deal. They know they can call Noel up, and we can talk shop. We wait for them to come to us, we don’t pay them for it. Drake wears our stuff, Snoop loves our stuff.”

It’s only at this point that Lee seems relaxed talking to us — we’re in familiar territory now. He’s speaking to his own experience, and you can see he’s a friendly guy. It’s clear why Snoop likes to call him up for a chat from time to time.

Lee’s passion

To this day, Lee is still hands on with projects that most CEOs might not even know exist.

“I kinda learned my lesson on passion projects, and avoid them. When the company is doing gangbusters, you can make the time to do those.”

“I started a record company, Monster Music, in order to further the audio experience — I was really passionate about surround. We partnered with some really good works, redid these projects.” Lee remastered some of these surround albums by hand, and others at the company are quick to applaud his sharp ear.

“We’re coming out of nowhere to compete with Sonos.”

It isn’t just passion for his company, either, Lee really extends it to his home in the bay, a big part of the reason that Monster purchased the naming rights to Candlestick Park in 2004.

“The city was looking for naming for Candlestick because Parks and Recreation needed money, so they had to close parks and cut back on maintenance and supervision. It wasn’t just a problem for the city’s employment, but also for the kids and the community.”

“I’m sure we didn’t have the highest bid, but we went in to the 49ers and said ‘I’m a native San Franciscan, I was born here. It would be a really synergistic thing for the city to accept us.’ It was four years, but they lost every game I went to. After us, it went back to Candlestick Park permanently. We did what we wanted to do, we put our name in front of a lot of people in the Bay area. We wanted to turn the park into a fun place to be, we did it for the fans.”

Looking forward

Lee knows it’s not all passion projects and hanging out with famous musicians though, there are some areas where Monster could be doing a better job. Lee still considers himself more of an engineer than a CEO, although he’s learned a lot during Monster’s growth. There are still business practices that need some work.

“We’re looking to shore up the things we’re not so good at. Marketing, supply chain, operational processes; we need to reinvent and reorganize.”

There’s also space for them to return to their roots as a company that enhances products that people use.

“Where we’ll go next is based on where hardware goes. Streaming music is really hot, so we’re going to be a part of that. It won’t be us doing it, it’s more about targeting areas that are popular and making them better.”

Before leaving behind the famous family photos and rows of patent approvals, Lee left us with one last thought, which neatly sums up 37 years of the Monster brand.

“Don’t skimp on the cables, don’t settle for ordinary.”