“Is there anybody out there?” “We don’t need no education.” “Hey you, don’t tell me there’s no hope at all.” “And I have become … comfortably numb.”

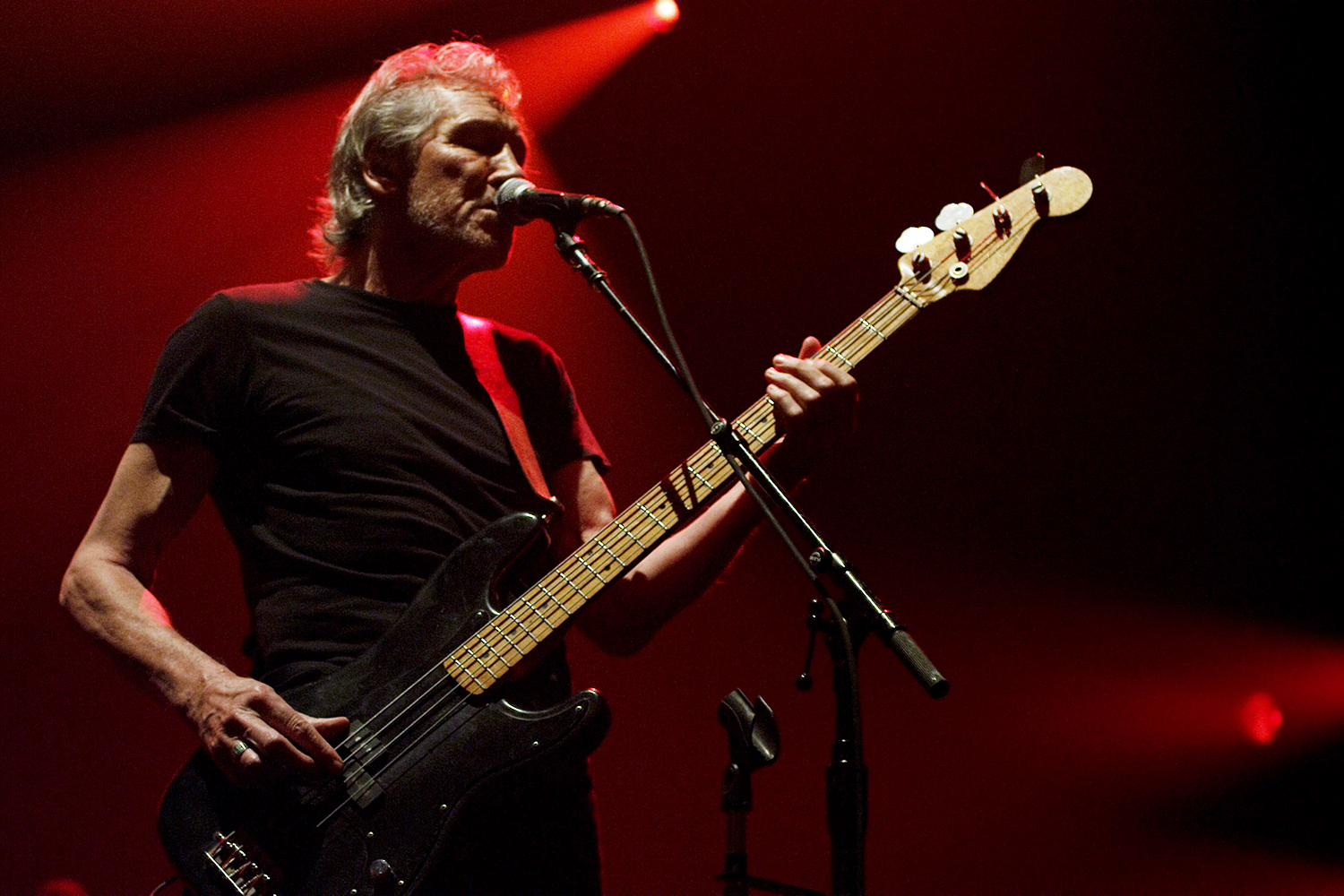

As if I even have to tell you, the above lines all come from Pink Floyd’s seminal 1979 masterpiece, The Wall. Roger Waters, the former Floyd bassist, vocalist, and chief sonic architect behind that legendary album, spent years visualizing and planning how to properly perform it in its entirety on the live stage. The resulting tour spanned three years starting in 2010, played to more than 4 million people worldwide, and pulled in over $458 million, the highest grossing tour of any solo performer to date. (That’s one comfortable sum.)

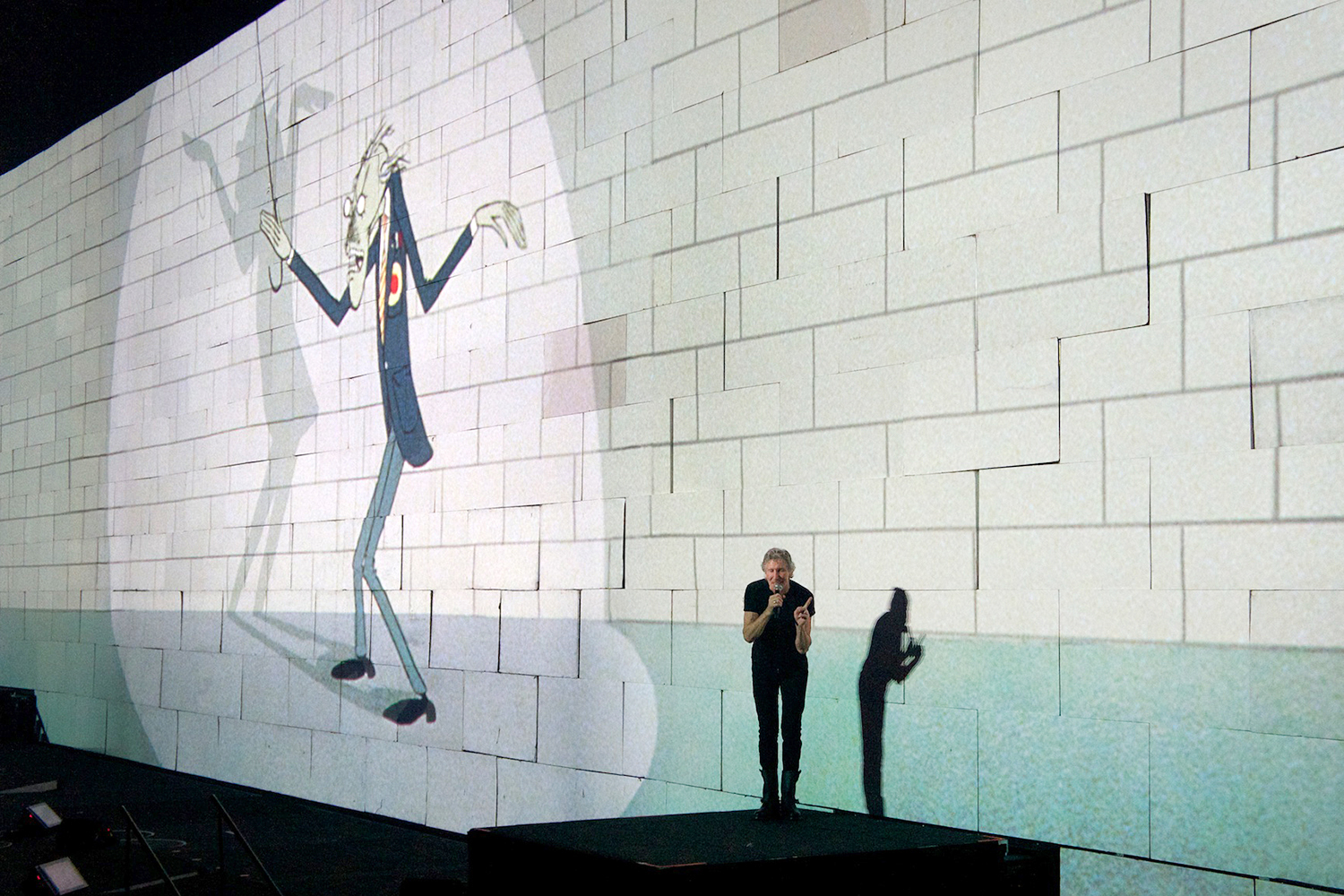

I saw The Wall live twice – once indoors at the Izod Center in East Rutherford, New Jersey in November 2010, and once in Yankee Stadium in July 2011. Without question, it was the most visually exciting and sonically pleasing large-scale arena/stadium show I’ve ever witnessed. Sound quality is always tricky in a stadium setting, but the live quad design utilized for The Wall experience delivered in every respect, from the — spoiler alert! — thunderous onstage plane crash that starts the show to guitarist Dave Kilminster’s elegiac, cleansing guitar solo atop the massive 500-foot-long Wall itself during Comfortably Numb.

If you missed the tour or want to see it again, you’re in luck, as Roger Waters The Wall will be premiering in theaters across the globe on September 29. Shot in 4K and mixed in Dolby Atmos, this Wall stands at the pinnacle of aural and visual excellence. There is also a narrative co-directors Waters and Sean Evans have interwoven throughout the performance footage: following Waters on his initial pilgrimages to visit the gravesites of both his grandfather and father, who were killed in action respectively in World Wars I and II.

“Everybody says, ‘I didn’t realize it was going to be like that,’” says Waters. “It comes as a huge surprise. It moves people, and they get it. They go, ‘Wow, that is really moving.’ If you can get through the story about the vet saying to me, ‘Your father would be proud of you,’ and then I say, ‘I’ll never forget him,’ and then you see the young girl with the peace sign reuniting with her father – I defy anybody getting through those two minutes without welling up.”

Digital Trends sat down with Waters at the Sony Club high atop Madison Avenue in New York to discuss the sonic construction requirements for The Wall, what happens when the band is actually performing behind the Wall, and his total disdain for streaming. You are only coming through in waves, but I can now totally hear what you’re saying.

Digital Trends: Timing for stadium shows is a tricky thing. I’ve seen a number of them where the time delays are off, but the sound design for The Wall was so spot-on for making sure the audience was fully enveloped by the experience no matter where they sat in the venue.

Roger Waters: That’s great. I love that. The technology, the software, and the programs that [production manager/sound engineer] Trip Khalaf and [PA system engineer] Bob Weibel used is all about delays. That’s the way you get clarity.

There’s also such a level of precision with the visuals and with where you’re positioned onstage. It all has to work together with the sound too, or we get taken right out of the story.

Yeah, but of course it’s different because sound only travels, what, 1,100 feet per second? That’s super slow compared to light, so there are always weird delays. The human brain will accommodate a certain amount of it, but what the human brain can’t accommodate is all the clutter of stuff coming milliseconds apart.

So we did invent something on this tour that has never been done before, and I call it False IMAG. [Image magnification] is always a bit distressing to people, as the delay that is built in is sort of weirdly irritating – about 60 milliseconds; that’s the fastest. But what you see, even if you’re in the prime position, is wrong. It looks wrong.

We were playing at an indoor football stadium in Copenhagen when I decided I really needed big IMAG. I said, “Come on, we’ll film some, just as an experiment. Film me singing, and we will take it to another place, and then we will project it in sync with me performing live.” So it’s not IMAG you see, but it’s me acting the same movements that are up on that screen.

That’s impressive! We’ll have to call it RMAG, then.

Yeah! So that meant I had to learn what I did, and then do the same thing every night. It’s just another technique, but it looked fucking great! It’s all in sync, and you think, “How did they do that? It’s great!”

It’s you and you up there, together! Did you have any specific requirements with the sound design as to what you wanted to hear during any particular sequence?

Absolutely. For instance, during Run Like Hell, Robbie [Wyckoff] would be singing, “You better run,” and I’d say, “That eighth-note triplet – repeat on it.”

“You are in the great elevator of commerce, and you have become the background noise.”

Also, just because I’m a good bit older now, we perform Run Like Hell in C instead of D. I’ve dropped it a tone, just so I can sing it.

Plus, your movements onstage are different.

Well, the movement doesn’t really matter – though it’s interesting trying to get the audience to clap along. That’s why I shout, “Follow me!” (laughs)

Right, audiences clapping out of time can really throw performers off.

Oh, trust me! Sometimes they were so off, you’d have to really, really concentrate so hard. Everything in the show is to click [track] – everything – so we got very good at working to click. When you ask people who aren’t used to working to click to do it, they’ll say, “Oh, it’s so hard to get any feeling.” Just fucking practice – you’ll get the hang of it!

Poor Snowy [White, guitarist], in “Brick 1” [i.e., “Another Brick in the Wall Part 1”], it’s almost the hardest thing to play – he’s going [mouths riff], “dig-a-dig-a dig-a dig-a…” Well, if you’ve got an audience clapping completely out of time – to lock into the click and stay with it is really hard.

In the middle of the show, the band performs a few songs behind the wall that’s been built onstage, and you can’t be seen by anyone in the audience at all while you’re doing it.

It’s one of those things that is great about watching the movie. Seeing Snowy’s solo in Hey You – he’s playing that note and then holding it, and everything else – no audience has ever seen it, because it’s behind a big fucking wall! (laughs heartily)

What are you hearing while you’re playing with that big wall right in front of you? Is it just what you get from your in-ear monitors, or can you also hear the audience cheering and singing along?

I have my in-ears in, but you can hear everything. Of course, it sounds different with a piece of cardboard in front of you. (chuckles) It’s very different. But we’re all very used to it, you know. We’re a big happy family, just doing our jobs. It’s actually very cool to be behind the wall, knowing that they’re out there.

I love the way they respond in Is There Anybody Out There? I think that audience might be in Athens, because they weren’t allowed to bring cameras or iPhones into the show.

And isn’t that a shame that it seems to be part of the show now – watching things through a phone or camera eye rather than directly at you, the performer?

It drives me crazy. It’s horrible, it’s terrible. If you want to see that crap, you can go look at it on YouTube, because yours won’t be any different than any of the other crap.

I understand people wanting to capture their favorite moments, but a production on the scale to this degree begs to be watched directly as often as possible.

I agree, it’s crazy.

I’m sure you’re not a fan of the streaming universe.

No, I am not. I’ve never been a big fan of piracy of any kind – that institutionalized plunder of artists and their work and their ideas by people who do it just because they can, and they can get away with it. And they do.

“Just fucking practice – you’ll get the hang of it!”

What you become is a tiny cog in a huge machine that has nothing to do with music. It has only to do with encouraging the consumption of other things. It’s advertising revenue. It has nothing to do with music – at all! And that’s why the artist is cut out of the equation, because the idea is what you’re doing is worthless. You just become a means to an end – and the end is for people to sell cars, and for other people to get rich. You’re just irrelevant. And so is the music. You are in the great elevator of commerce, and you have become the background noise. So fuck you! (laughs heartily)

How do you as the artist say “fuck you” back at the system and take back control?

Oh, I don’t know, I don’t know. But I’m glad that they can’t invade the world of my show or the world of this movie. They can’t do it. They don’t know how to do that. And people do value it, so they will pay to get their bum in a seat to have that moment or the two-and-a-half hours of that experience.

You’ve been working on some new music. Will you take it out on the road?

I don’t see myself going out into stadiums again, but I could do an arena show where it’s more controllable. It would probably be an hour of new theater and music, with probably nearly an hour of old music.

Would you do a full album sequence as you did on The Dark Side of the Moon Live tour [in 2006]?

No, what I would do is interweave old songs into the new narrative. Because, I’ve been thinking about this – if I do go out again, I’m not sure people would want me to go out and do two hours of stuff nobody’s ever heard before.

I completely understand people would want to hear some new stuff, particularly if it’s got context; they get that. But I’m lucky in that, because I’ve been writing so long, and people recognize my style – if I’m writing a new song that’s based around the basic question, “Grandpa, why are they killing the children?”, you can put Us and Them in there, or Money, or any number of songs from Dark Side of the Moon or Amused to Death or Wish You Were Here. Welcome to the Machine – any of that stuff that people want to hear, and want to remember. It all fits, simply because it all comes from the same beating heart. The same bleeding, beating heart. (smiles)