If there’s one event that can help you understand the discord between the Internet and music industries, it’s SXSW. At one bar, you’ll get to discover the local up-and-comer, and at the next, the corporate sponsored, Twitter-promo’ed star who’s been headlining tours for years. And in the mix of it all are the likes of Pandora, Spotify, and Grooveshark – the streaming companies that have defined (and in some opinions, destroyed) the lay of the music land.

If there’s one event that can help you understand the discord between the Internet and music industries, it’s SXSW. At one bar, you’ll get to discover the local up-and-comer, and at the next, the corporate sponsored, Twitter-promo’ed star who’s been headlining tours for years. And in the mix of it all are the likes of Pandora, Spotify, and Grooveshark – the streaming companies that have defined (and in some opinions, destroyed) the lay of the music land.

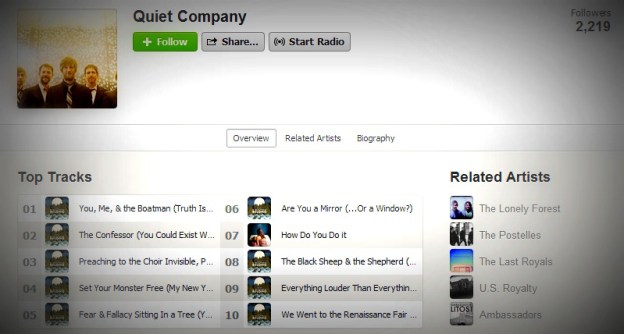

The way bands navigate this new terrain is both necessary and terrifying – just ask local Austin indie-folk group Quiet Company. “I kind of feel that if the Internet were one person … I do feel like someone would be obligated to assassinate it,” says frontman Taylor Muse. “It does great things, but it also ruins everything it touches.”

He’s speaking, of course, of how digital music consumption has turned albums into files, and listeners into users. “I think for years now, as far as back as [Quiet Company] has been together, people have been talking about how different the music industry is and how the Internet has changed everything and how we’re all looking for a new model.”

“After everything, I’m not sure there is a new model. The old model is still the model, it’s just that the Internet made it way worse.”

To be certain, Muse and Quiet Company have a love-hate relationship with the intersection of music and technology. About two years ago, at SXSW as fate would have it, Grooveshark approached the group about a partnership in which it would hugely promote them to its users. “They said they were starting an artist development program,” band manager Paul Osbon says. “In part to show that, you know, you don’t need a record label to get exposure. And we were sort of the guinea pig for that.”

The group worked with Grooveshark (a streaming site like Spotify) for 18 months, even releasing an album with the company’s help (and heavy promotion). “In about three months, we went from 2,800 Facebook fans, to 55,000,” says Osbon. Thanks to the partnership, Quiet Company has amassed a huge following in Spain, and found new fans it never would have.

But now the contract is up and not being renewed, because – you guessed it – a monetization strategy couldn’t be found for Grooveshark. “We were the test monkeys,” says Osbon. “It didn’t go like everyone thought it would, but it still ended up being great for us.”

Not only for the exposure, but for the analytics. Despite any ill will toward technology from his band, Osbon has known the power of social metrics. “They gave us tons of info – what type of toothpaste our listeners used, what shoes they wear. If they had found a way to translate that into sales, and market that…”. Osbon says that Quiet Company makes a considerable amount of its revenue off of merchandise sales, as well as increasing digital sales. Strangely, he also tells me that vinyl sales are going up – oftentimes from fans who don’t even own record players but want to keep the records as mementos.

While these speak to Quiet Company’s growth, a streaming parternship doesn’t appear to be in the band’s future. Quiet Company remains the only band Grooveshark has poured its efforts into, and Grooveshark the only streaming site Quiet Company has officially partnered with. And it might be the last, given it frontman’s feelings toward the collective market, which can be summed up as “a necessary evil.”

Muse doesn’t like Spotify and it’s invading ways, or Facebook and it’s selective News Feed attitude. But Quiet Company are not luddites – in fact, they’re just picky. “What really made music social, when we debuted tracks for our last record, was Turntable.fm. That was super cool!,” Muse says. “We got all our fans in there and it was so fun to me, and such a natural way to say ‘hey, we actually care about this band, you should check it out, and here’s some of our music too.'”

He and Osbon both also mention TheSixtyOne, a now-very quiet site that used game mechanics to win bands new fans and elevate them to homepage status on its site.

And of course, before there was Spotify or Turntable.fm – before there was even Facebook (can you even imagine such a time?) – there was Myspace. “Myspace was always better for bands than Facebook,” says Muse, echoing, easily, every band ever. Of course, both Muse and Osbon admit they currently don’t use the band’s old Myspace account because they can’t access it or remember the password. They plan on getting on board with the new Myspace, but wonder – as everyone else has been – how or when their fans will get there.

Muse and Osbon’s real disillusionment, however, is with Facebook. Their gripes are familiar: What “other” inbox are you talking about?! How few of my friends and followers see my posts a day?! You’re going to charge me to message people?!

I tell Muse, who isn’t a Spotify fan, that the streaming application is actually how I began listen to Quiet Company. He and Osbon consider it, and then challenge me – but do I buy music? The answer, as most members of my generation would agree, is rarely. However, I counter, I buy far more concert tickets and merchandise than I likely would. I also take a lot more interest in the people making my music, following them on Tumblr and Instagram. Both seem to appreciate this point, but I’m mostly playing Devil’s Advocate, because I share in their frustration. I don’t own my music; it’s content I’m borrowing from Spotify’s cloud – and if Spotify doesn’t have rights to something I want, well then I’m out of luck and forced to move on to the next streaming client and start yet another account – which I’m unlikely to do. Instead, I’ll just forgo listening.

“It’s all become so disposable to listeners,” says Osbon. “You don’t like something within the first 30 seconds, you delete it or skip it and move on.” And he’s right: Entire catalogs of music wait before me to be consumed, why waste time? Because, they argue, there’s an appreciation that comes with age. “Most of my favorite bands, I didn’t like them the first time,” says Muse.

While Quiet Company owes much of its exposure to the Internet, they also have plenty of their own hangups when it comes to navigating this ever-changing landscape – just like every last one of us. But just like every last one of us, they know they can’t avoid it.

“You have to use social networks,” says Osbon. “People sort of think it’s like selling out – but everybody thought licensing was selling out, too. But you really have to do it.”