“Zombie is probably even more relevant now, especially after all that happened after September 11.”

Good songs engage, great songs endure. When it comes to discussing the super-popular canon of Irish alt-rock icons The Cranberries, however, perhaps we need to substitute the word “linger” for “endure” as a nod to one of their most impactful and long-lasting songs.

The Cranberries recently decided to revisit that storied catalog on Something Else

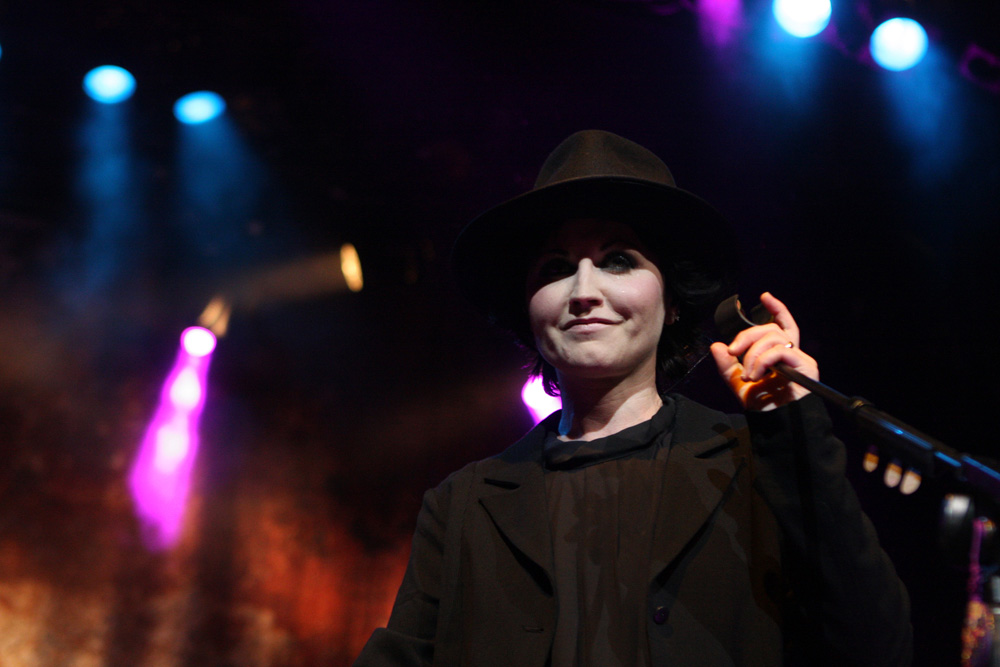

“It’s a challenge that breathes new life into the songs,” Cranberries lead vocalist Dolores O’Riordan told Digital Trends about the impetus behind cutting Something Else. “It’s also nice because there’s a whole new generation of people who wouldn’t have heard those songs before, so maybe it might also reach a younger audience.”

O’Riordan called Digital Trends from Southern California to discuss how The Cranberries recast indelible songs like Linger and Dreams, the ongoing universal imprint of Zombie, and the best ways to ensure vocals feel fresh and not canned. My life is changing every day in every possible way…

Digital Trends: As the Cranberries’ primarily lyricist and lead singer, did you have specific ideas you wanted to get across when working with the string section as to how you wanted those songs to sound differently?

Dolores O’Riordan: Yes, I always have the idea that it has to sound like a mood, you know? And it’s important to get the right rhythm to make it sound a little more “creamy.”

I like that description. Let’s start with the very first song you ever wrote, Linger. What’s making that drone sound at the beginning of the track on Something Else?

It’s actually a violin. Linger was easy enough because the original recording has a quartet on it, so the chamber orchestra just played what was on the original recording.

This version starts off with an acoustic guitar and a violin. The violin is playing a high note there, though I’m not sure which one it is — probably a D or something, since the song starts in D major.

Then you follow that classic with The Glory, one of two new tracks on the album.

I love the melodies in The Glory, and the chords Noel [Hogan, Cranberries lead guitarist] came up with for it. Noel tends to write these open chords that leave a lot of space, and in those spaces, I can find my melodies and my notes. Sometimes I can hold one note, and everything moves around that note. I don’t have to keep moving.

Was everyone in the same room while you were recording? Was it all cut live?

No, though we tried it. When we first got the idea, we went into the studio and the vocals and drums were set up in the room. And then we had the quartet set up in there, and next added the guitar and bass. But it just didn’t work because everything was bleeding into the one microphone. The sound was bleeding everywhere.

So, I wound up doing my vocals separately. They’d send me the beds with the bass, the drums, and the guitars, and I’d do my lead vocals next. After that, the quartet would come in and lay down their parts.

And in some cases, you chose to double your vocals.

Yes. Sometimes that can be effective in the choruses, like it is in songs like Zombie.

In this version of Zombie, I really feel your emotion coming through each word. Each one of them really seem to have an extra weight to it, wouldn’t you agree?

Yeah — and it’s bizarre, because I did it really quickly, only two or three times. My partner [Oleg Koretsy] comped up the vocals, and sent it over to Ireland for the quartet to play over it. Those vocals are very fresh. I didn’t dwell on them. I didn’t labor over them as much as I wanted to have a good delivery.

I think a lot about David Bowie’s albums where sometimes you can hear the pops and you can hear him breathing, which keeps it nice and fresh; it’s not trying to be technically perfect. At this stage, my fans know who I am and they’ve seen me live enough to know what I’m like performing. For me, it’s more of a case of “Keep it natural, keep it real,” and try to give a good delivery.

I prefer hearing the singer’s character come through in their lead vocals. I know some producers like to clean things up and take those kinds of things out, so I’m glad that when you do what I call the “Dolores growl” whenever you sing the word “zombie,” there’s an added weight to that vowel sound you’re getting there.

We all have to take a breath every now and again.

Yes. I think when it’s too clean — when people go in and try to clean up the breath to make it sound seamless — it takes away from the reality. And in reality, nobody’s perfect. We all have to take a breath every now and again.

Sometimes you might even have a little nuance in your vocal where you go, “Ooh, what was that?” It was just natural, and that’s what keeps the thing alive, you know?

Yeah. I always think of the background vocal that Merry Clayton sings on [The Rolling Stones’] Gimme Shelter, the place where her voice cracks. That’s a real moment, so it had to stay in there as is.

Yes! And I always liked Bob Marley. There’s always something a bit raw about Bob Marley, and you have to keep it like that, keep it real — not too polished, too perfect, or too produced.

Do you listen to any music before you perform live?

When I go on tour, I listen to Bob Marley before I go onstage because that puts me into a good mood. I’ve been listening to Bob Marley before every gig for about 10 years. Seriously! (chuckles) I listen to him when I’m putting on my makeup and getting ready to go onstage.

Was there one record when you were growing up that was the one you’d consider got you into music in the first place?

No, not really, because I started off with traditional Irish music, and when I went to school, I started off by playing the Irish tin whistle. I took up a lot of instruments. Next I messed around with the spoons and the bodhrán [an Irish frame drum], and then I started playing the piano at age 12.

And you were classically trained?

Yes, I took piano lessons. I went to Grade 4 in Practical and Grade 8 in Theory.

Would you say that training influenced the way you hear songs and create melody and structure?

I think that it definitely helped, because you have a fair idea about certain structures and you hear different melodies in your head. But I also played the church organ, and I loved playing the Latin hymns. They had great melodies — the Gregorian chants.

But when I was 16, I got into bands like The Smiths, The Cure. R.E.M., and Depeche Mode. My tastes really haven’t changed that much. I think I’m stuck in a time warp from when I was a teenager or when I was in my early 20s. (laughs)

I think we can hear those influences in The Cranberries — and especially in the D.A.R.K. project, the band you had with Andy Rourke of The Smiths and Oleg Koretsy. I thought Gunfight was a great song, and I’m hoping we might get to hear some more of that music someday. Maybe now that we’re talking about it, people will go look it up online or find it on one of the streaming services and get into it that way. I bet a lot of them would go, “I don’t know why I missed this, but I really like it.”

I’d like that. D.A.R.K. was a side project, but it kind of fell apart, and it just didn’t make it. I really liked it, so maybe we’ll re-release it and give it another chance. It was interesting to work with Andy, who was one of my icons.

Is it sad or ironic, or whatever the right word is, that Zombie seems to be as relevant in 2017 as when you first wrote it and put it out in 1994? People continue to follow certain belief systems blindly, it seems.

Yeah, it’s probably even more relevant now, especially after all that happened after September 11. There’s a lot more paranoia now about terrorism in the world. Going through things like security in airports has turned into quite the ordeal. Before that, everything was more laid back.

We had our own problems in Ireland, but they were in Ireland; they didn’t come to America at that stage. Before that, life was more free and easy-going. I tell my kids about the times when I was a teenager, where I remember the pilots on the planes telling me to come up and talk to them in the cockpit. I’d go up there, sit down, and just be chatting away. It was all so laid-back and pure, but not anymore. It’s a different kettle of fish now.

That’s so true. If you approached the cockpit to get your little wings from the pilot, somebody might tackle you before you even got to the door. It’s a lot scarier now.

It is; it is. And you can’t blame people for being paranoid. You have to be paranoid now. It’s a totally different thing.

I do think about Zombie to some degree whenever I hear the most telling line from Free to Decide: “I live as I choose, or I will not live at all.”

“I do what I want to do, and I’ll do it my way.”

Yes. I was pig-headed, wasn’t I? (laughs) That spoke to my pig-headedness and stubbornness, because when we got really famous, there were all kinds of people telling us what to do, but I was always like, “I do what I want to do, and I’ll do it my way. I won’t do what you tell me!” (laughs again)

Finally, I have to say how much I like how Dreams is now more modernized. I was almost singing some of Lou Reed’s Street Hassle in the part the string section was doing there, though.

That’s right. The string section added some nice melodies and textures that weren’t there before. That makes them all a little bit new, you know?

And isn’t that the mark of a good song? You add some things to it here and there, but if it’s got a solid base at its core, it will continue to resonate with people.

Yes. If it has a good verse and a good chorus, you’re almost there. Add some structure and a good delivery, and then you’ve put some icing on the cake.