While CDs have been on their way out for some time now, this week’s news may as well be a eulogy for the once-mighty disc, signaling a last step in its passing from a dominant medium to a forgotten relic in the ever-changing pantheon of recorded music. Many of us have rich memories of our time with the Compact Disc, from the first cartridge we cracked open outside a Sam Goody, to the overstuffed wallets and CD towers in our living rooms that stored hours upon hours of digital music bliss.

As such, we decided to see the CD off in style with this trip down memory lane. Follow us below as we chronicle the rise (and demise) of the late, great, Compact Disc.

The CD is born

Most often attributed to inventor James Russell, the CD evolved from multiple optical mediums, and was eventually finalized in 1980 when Sony and Philips created the famed “Red Book” standard, which was a series of documents that outlined a 120mm diameter disc bearing music at a resolution of 16 bit/44.1kHz. The sample rate is based on the Nyquist theorem (shout out to our fellow nerds), which, in this case, outlines the minimum rate needed to replicate all frequencies humans can theoretically hear. The resolution is still regarded by many as the optimal digital standard. The CD, however, wouldn’t officially make its way to the greater public until 1983.

The CDP-101: Sony creates a legend

The first commercially available CD player, the iconic Sony CDP-101, was first offered by the electronics giant in Japan in October 1982. Born, as Sony states, nearly 100 years after the first phonograph player, the CDP-101 made its way to the U.S. (and across the globe) around six to seven months after its initial debut in 1983, and was priced as high as $1,000.

CDs take over

Following an initial offering of around 20 available albums at launch, the CD exploded over the next few years. As reported by The Guardian, the CD’s unofficial arrival came with the release of Dire Straits’ Brothers in Arms album, which was recorded on the latest digital equipment and spawned a tour sponsored by Philips. Released on CD in May 1985, the hit album became a musical mainstay, and vinyl fans and audiophiles began to purchase CD players in droves to adopt the growing format. By 1988, CD sales eclipsed vinyl, and overtook the cassette in 1991.

A very big box

Those around for the CD’s rise no doubt remember their first purchase (the Sliver soundtrack — don’t judge). But perhaps just as memorable was the packaging in which it arrived. Comprising six-inch by 12-inch casings of cardboard and plastic, the so-called longbox packaging was several times bigger than necessary. The design was, in part, an effort to make it easier to flip through discs on shelving units designed for LPs, but it was also aimed at theft prevention. Longbox packaging was estimated to be responsible for creating 18.5 million pounds of extra trash each year and, after much public outcry, was eventually replaced with plastic “keeper” boxes of the same size that store clerks would unlock. Eventually, the keepers would go away and leave only the cellophane-wrapped jewel cases we think of today (with magnetized security sticker attached).

The magical CD-R

Old timers will also remember the moment in the late ’90s when we first discovered the CD-R (Compact Disc Recordable). Developed in 1988, the CD-R took flight when PCs and digital recorders began allowing consumers to “rip” discs, preserving the music in low bit-rate files to later be recorded onto CD-Rs to share. The sound quality was low, and it could take as long as 8 hours to write a single disc from a PC drive, but with an average cost of about $17 to $20 per CD in stores, it didn’t take long before these discs, readable by any CD player, became a mainstay. As the first readily available way to share digital music (without actually paying for it), the CD-R was in many ways a steppingstone to the end of CD dominance.

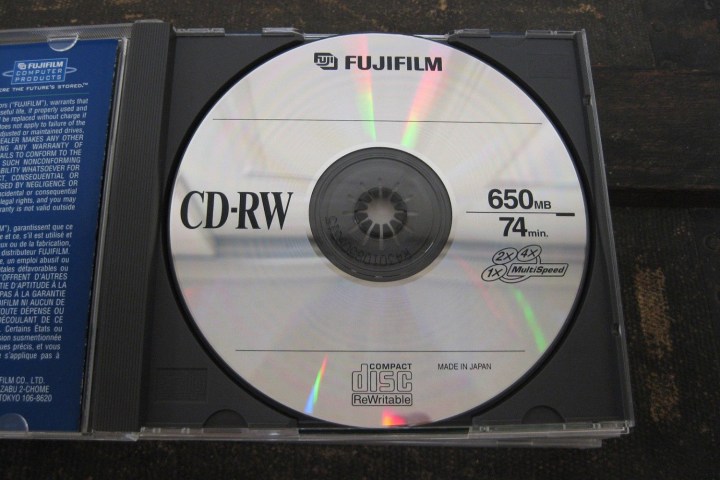

MP3 plus CD

The next big ticket was the CD-RW(Compact Disc-ReWritable), which, when combined with Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft’s popular (and tiny) MP3 file format, faster optical disc drives, and more advanced CD readers, allowed for a smorgasbord of music to be available to listeners for free. All you needed was a pack of CD-RWs and you could load hundreds of songs from a friend’s hard drive onto each disc, which could be played by newer CD players, and/or easily shared with others. Sure, you had to spool through dozens of artists while idling your car to find the tune you were after, but suddenly music was free, and it was (almost) everywhere. There was just one last piece of the puzzle needed to create a free-music revolution that would help spell the demise of not only the CD, but the music industry’s entire sales model. And we bet you can guess what we’re talking about.

Napster: The great disrupter

In 1999, just as millennials and the internet itself were coming of age, Napster hit the web and changed the world forever. Allowing a network of global users to easily share music files, the site boomed as the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) and other major industry organizations scrambled to catch up (and fetch their high-dollar lawyers). At its height, Napster hosted around 80 million users, and paved the way for other peer-to-peer sites like LimeWire, uTorrent, and many more. While Napster was eventually shuttered in 2001, the genie was out of the bottle, so to speak, and the piles of cash that CD sales had hauled in began to slowly but surely fade away.

Steve Jobs and his big little pod

In October 2001, amid this confluence of assaults on the beleaguered CD, Apple’s forward-sighted innovator Steve Jobs unleashed perhaps his greatest creation to that point, the gorgeous little MP3 player known as the iPod. In true Apple fashion, the iPod was far from the first of its kind — and some might argue it wasn’t even the best — but paired with Apple’s new iTunes music app, the iPod took the world by storm to become the must-have music accessory. Perhaps just as striking, iTunes sales became a musical powerhouse for Apple, engorging its coffers and changing the way people purchased music — for those who still did pay for it. In 2005, iTunes outpaced CD sales in two major physical stores for the first time. But the modest victory would be short-lived.

The streaming revolution

Pandora’s inception in January 2000 spawned from the Music Genome Project, an “internet radio” service following an algorithm that categorizes music with hundreds of characteristics to serve listeners music they’ll like based upon artists, songs, and simple thumbs-up or thumbs-down ratings. The first major on-demand service, Spotify, came eight years later, and together, the two companies helped rewrite the music playbook. Offering free/affordable music to anyone online — without the need for breaking the law or storing massive amounts of data — music streaming quickly became an industry giant. In 2014, streaming revenue eclipsed CD sales for the first time, and did the same for digital downloads in 2015.

An uncertain future

Yet, as the physical CD readies to slide into its saddle and ride into the sunset, the music industry is still in relative disarray. Spotify, the biggest on-demand streamer by leaps and bounds, has yet to turn a profit 10 years on. And while Apple’s catch-up service, Apple Music, continues to gain ground , it too appears to be a loss leader for the mighty company. Will streaming ever become a profitable vessel for the industry at large, or is the Napster wound simply too deep to heal? And just what happens if streaming services never make money?

Unfortunately, we can’t answer those questions. Instead, we can only bid adieu to the once-mighty CD. Goodbye, old friend. You served us well.