“When I heard the Pixies for the first time, I connected with that band so heavily. I should have been in that band — or at least in a Pixies cover band.”

That was the late Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain, talking about his deep reverence for the Pixies, the pioneering four-piece alternative rock band from Boston who honed and shaped the loud/soft/loud song dynamic that Nirvana cut to perfection on their seminal 1991 instant-gamechanger, Smells Like Teen Spirit. Cobain freely admitted to Rolling Stone that “I was trying to write the ultimate pop song. I was basically trying to rip off the Pixies.”

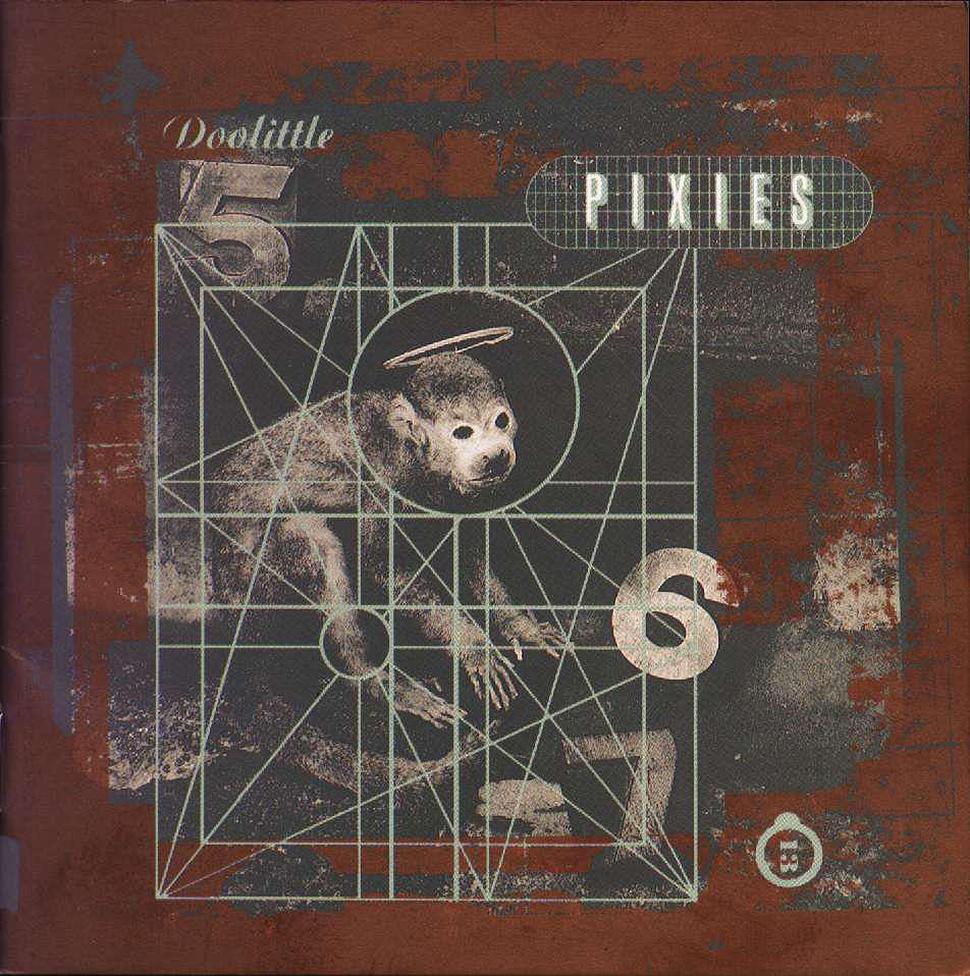

And while Nirvana indeed took Teen Spirit into the pop stratosphere and beyond by transforming the swerve and verve of then-rock culture from hair-metal swagger to alternative angst-o-rama, it was the Pixies — singer/songwriter Black Francis (born Charles Thompson, a.k.a. Frank Black), guitarist Joey Santiago, bassist Kim Deal, and drummer David Lovering — who really set the tone for the ’90s template many indie bands continue to follow today. That blueprint can be found all over their second album, 1989’s Doolittle, from the caterwauling crunch of Debaser to the angular harmonics of Here Comes Your Man to the twisted parable of Monkey Gone to Heaven to the punk fury of Crackity Jones.

It was the Pixies who really set the tone for the ’90s template many indie bands continue to follow today.

To celebrate the album’s 25th anniversary, the triple-disc, 50-track Doolittle 25 collection (out today via 4AD and also available digitally) commemorates this pivotal album’s ongoing impact with an ace remastering job in addition to scores of unreleased demos, B-Sides, and key Peel Sessions. Yes, there’s indeed a lot to love about Doolittle.

Digital Trends rang up a pair of Pixies to get the lowdown on why Doolittle endures. Today, in Part 1, Santiago, 49, tells Digital Trends how silence is a crucial element of the band’s signature sound, why you should avoid MP3s, and shares the secret behind “The Hendrix Chord.” In Part 2, which we’ll publish later this week, Lovering, 52, will have his say about Doolittle’s ongoing legacy. Gouge away and stay all day, if you want to…

Digital Trends: Did you ever think there’d be such fanfare about Doolittle 25 years later?

Joey Santiago: The only thing we knew when we recorded it was we were fairly proud of it, you know? The goal, when you’re in the studio, is to record something that’s going to last forever. And we happened to hit the mark.

Did you have a particular sound in mind for yourself when you started working with producer Gil Norton? Did you give him some pointers on how you wanted to sound on this record?

I just wanted the guitar to be dry, not affected — and we did that. I went straight into the Marshall amplifier I had at the time. Just a guitar cord and the amp.

Early on in the sessions, was there a point where you went, “Ahh, Gil’s got the dry sound that I want”?

I think Tame is the one where I really, really noticed it. And that song has to be dry. For what I play there, it wouldn’t have made any sense any other way. It’s a very aggressive sound.

Besides the physical three-disc set, we have high-resolution downloads and a 180-gram vinyl version of Doolittle 25. What’s the best way to listen to this collection? Personally, I’m hearing more of the details in hi-res.

Oh yeah, the remastering is great. To be fair, I hardly listen to our records, but we listened to Doolittle so many times at the studio, and we were just blown away. In fact, Gil taught us how to rewind the tape and listen to it the right way. We just could not stop listening to it.

“When I put on a vinyl record, I pay attention to it. It’s not background music. And you’re gonna have to flip the thing over.”

You do lose the subtleties on MP3, yeah. It becomes exhausting listening that way, because the waveform isn’t smooth at all, with all of the different steps. MP3s are just not conducive to active listening. That’s what I think. When I put on a vinyl record, I pay attention to it. It’s not background music. And you’re gonna have to flip the thing over — the physical aspect of flipping it over (laughs), but the ritual is worth it, you know? It sounds great! Putting it on, dropping the needle — ritual de habitual.

I’m with you on that. I call it appointment listening whenever I put a record on. No distractions allowed.

Exactly! I have a chair that’s perfectly aligned, and I just sit back. I’m in the perfect spot, and I just listen.

Me too. You have a really good sense of when not to play and let the songs breathe, like letting Francis sing the lines alone or let Kim’s bass line come in before you strike. Is that a conscious compositional thing when you were listening to the demos — how you put yourself in the mix?

Yeah! It was very thought out, yes. I scribbled something at our rehearsal place — this is very deep, man (chuckles) — I said, “When you’re not making any sounds, you are.” You actually are. Silence is a part of the deal. It’s a sound that you’re making — it’s more of a statement. It’s a rest. It’s on there in the musical notes, on the music sheet, transcribed as a rest. It’s part of the musical vocabulary.

Point taken, though — a lot of times, you could have been winding out throughout the entirety of certain songs and totally changed the vibe of them by overplaying.

Exactly! Back then, it was heavy-metal time where people just played constantly on stuff, and that didn’t turn us on at all. Maybe that was the conscious effort — to sound different than the rest of the pack.

That kind of reminds me of the way Andy Summers played in The Police — he took a very minimalist approach to his chordings and his solos, and I think a lot of people may have underestimated the power of that in the context of the song itself and how he compared with other, flashier players.

Yeah, yeah, I can see that. Especially in the studio, when we were practicing, we’d hear the groove of the bass and the drums — and it was groovy, and cool, and we didn’t want to ruin that. At points, we just wanted to have people groove out, you know?

“We doubled up with two different guitars, and it just gives it that je ne sais quoi.”

I’m thinking one of the better examples of that has to be Monkey Gone to Heaven — knowing where to come in and add the power to the choruses and let the verses just breathe.

Exactly, exactly.

Was that solo doubled?

I think that one might have been a single, but I know we doubled up a lot. Once you start doubling guitars, it becomes pretty addictive, you know? It’s like, “Ohhh!” We doubled up with two different guitars, and it just gives it that (pauses) je ne sais quoi.

In 2009, you toured to celebrate the 20th anniversary of Doolittle, and you’ve pretty much been on the road fairly regularly since then. Do you have a particular favorite track on the album, one that you could play every single night of your life?

Well, unfortunately, we hardly do this one song that’s called Dead.

Oh yeah! You have a great, eerie lead on that one.

I love it. I just go by one word, “dead,” and I went with the Psycho vibe, you know — Bernard Hermann, the shower scene? (sings the creeping Psycho strings sound) I mimicked it with what I was doing throughout that song.

You got some good feedback in there, too.

Mmm, yeah. Love doing that. Those are hard to do in the studio. (chuckles) You have to find the perfect spot to be in.

And then we get a bit of a different vibe on Crackity Jones, where you guys are totally punking it out.

Yeah, that was just Charles, punking it out. There were a cluster of chords on that one, and he did say, “Well, Joe, good luck with this one.” (both laugh)

But, hey, you were up to the challenge.

Oh yeah — the more clustered the chords are, the more challenging it becomes.

Earlier, you were telling me how much you liked vinyl. What kind of turntable do you have? What’s your setup?

I’ve got a VPI ’table with a Benz Micro [cartridge] — those are beautiful.

“We do have a young audience. Maybe the young people just have more energy to put up with being upfront.”

Oh yeah, those are great. I have a PerspeX ’table with a Blackbird cartridge myself.

Ohhh! Nice, nice! The stylus is the most important part, because that’s the first thing to touch anything, you know? The other thing I like about vinyl is that if there’s some kind of catastrophe and you couldn’t listen to music, you couldn’t do anything with a CD or a download, but you could make some kind of pointy thing and spin the vinyl around to listen to it.

Right, you’d have to find something like an arrowhead, and spin the record on your finger —

Yeah, I like that idea. (both laugh)

No argument here. I’m glad Doolittle 25 is coming out on 180-gram vinyl, which you must love. Did you give any directions for that mix?

Yes, 180-gram is a good thing. You get more bass out it. The only thing I said was we probably should half-master it, on 45. That’s the ultimate hi-fi experience.

Listening to tracks like Mr. Grieves and No. 13 Baby — which is probably my favorite song on Doolittle — I don’t immediately get a sense of, “Oh, that was cut in year BLANK.” It could have been cut at any time.

Oh yeah. We avoided that because we wanted our sonics to be timeless, so that you couldn’t put a date on the music. That’s the production value of it. The songs are usually timeless, but more than anything, the production will give things a date.

True. Any time I hear a gated drum, I go, “Ok, that’s so 1984.”

In the ’70s, I remember thinking, “Oh my God, what’s happening to music?” [Elton John’s] Philadelphia Freedom (1975) was the last good recording before it all changed to disco — it all changed. All that bullshit reverb and other things going on. It was like, “Oh no! What are these guys doing?”

It would be interesting to hear you guys do a mono fold-down mix of this album. I could see how a song like Silver, which has that Western twang to it, would be really interesting in mono.

That would be interesting. That would be cool. Any song would be cool in mono. And I love stereo too, obviously. Quadrophonic never made it. (chuckles)

There was always something missing in quad mixes. But the surround format really gives you the broad scale of separation of instruments, plus the feel of people recording in a room together. Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull and I have talked about this a lot.

Surround, for — (pauses) … well, I don’t want to label them — but surround for prog like Jethro Tull and Pink Floyd makes a lot of sense.

Without a doubt. So where do you think the newer generations are discovering your music? YouTube, Spotify?

I have no idea. We do have a young audience, predominantly younger than the older folks. Maybe the young people just have more energy to put up with being upfront. (chuckles) Maybe it’s a combination of them knowing Nirvana was heavily influenced by us. They keep saying that everywhere. And also maybe Fight Club. [Where Is My Mind plays during the 1999 movie’s final scene and over the end credits.]

And that Nirvana myth just keeps on growing.

Yeah, I love it. I love it. They’re such a good band. They might have only done one song like us, Smells Like Teen Spirit, but they took it to a good level. I gotta hand it to them. It’s not that derivative at all.

I look at it like parallel lanes on a highway. You guys went on your own exit, and they went off on theirs.

Yeah, exactly!!! That’s cool. You just gotta be different — as different as you can.

“The 6th interval, the devil’s interval, that people thought it was — but I like that. Maybe the evil aspect of that chord is what I love.”

Like I was saying earlier, you understood how to create a sense of space in an arrangement, making songs a little more special than playing the same thing for 2-and-a-half minutes. Actually, hardly anything on Doolittle is even 4 minutes long.

As long as a song takes you on a journey, it doesn’t have to be that long. One of the examples Charles had was, “Listen to the Box Tops — The Letter.”

Right, that’s not even 2 minutes long! [1:58, to be exact.] Every note counts. Like Buddy Holly, too. I think Rave On isn’t much over 2 minutes long, if even that. [Rave On runs 1:47.]

Exactly! You get enough information.

Ok, real quick, last thing — can you give me the definitive statement on what you call “The Hendrix Chord”?

(laughs) I just love it! When I learned Purple Haze, I went, “Wow, this chord is pretty cool!” Obviously, it’s like the difference between a minor and a major. A minor sounds sadder, but that chord to me just has a neutral feel, and it’s got that interval — the 6th interval, the devil’s interval, that people thought it was — but I like that. Maybe the evil aspect of that chord is what I love.

“Then God is 7,” as somebody else has said [a line near the end of Monkey Gone to Heaven].

(laughs) Hah! Yeah, that’s right! You got it.