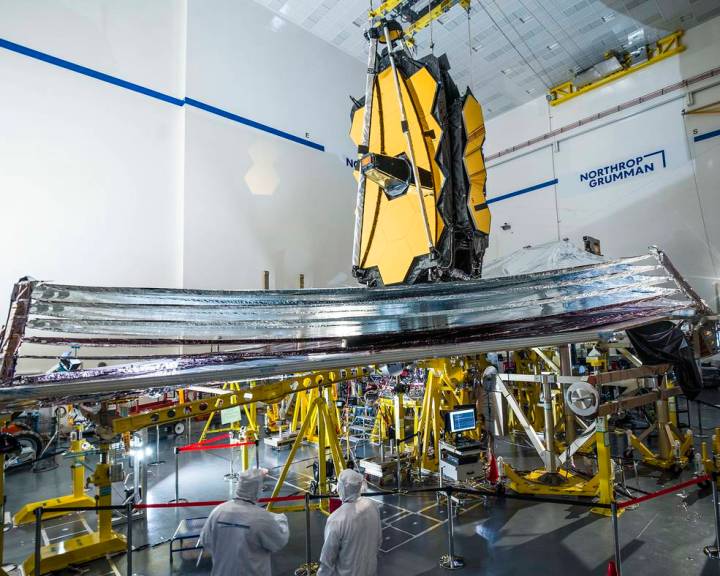

Progress on the testing of NASA’s next-generation telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope, is back underway after delays this year due to the coronavirus pandemic. Recently, the James Webb unfolded its massive sunshield in a series of tensioning tests which prepare the telescope for launch next year.

The latest test involved the telescope deploying its tennis-court-sized sunshield which will protect the delicate electronics of the telescope from the heat of the sun. “This is one of Webb’s biggest accomplishments in 2020,” said Alphonso Stewart, Webb deployment systems lead, in a statement. “We were able to precisely synchronize the unfolding motion in a very slow and controlled fashion and maintain its critical kite-like shape, signifying it is ready to perform these actions in space.”

The testing involved running the hardware through its paces, including the 139 actuators, eight motors, and thousands of other components that control the complex unfurling process. The testing is further complicated by the fact that in space, the unfurling will happen without gravity, but here on Earth, the gravity can cause friction issues.

The telescope, which will be a successor to the Hubble Space Telescope and which will search for habitable worlds among other scientific objectives, has been hit with a series of delays, including work on the project being suspended due to the coronavirus. But work is back underway now, with the team at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland performing tests on the hardware to ensure everything is ready for launch.

The team is hopeful that the launch of the telescope can go ahead in 2021. “This milestone signals that Webb is well on its way to being ready for launch. Our engineers and technicians achieved incredible testing progress this month, reducing significant risk to the project by completing these milestones for launch next year,” Bill Ochs, project manager for Webb, said in the statement. “The team is now preparing for final post-environmental deployment testing on the observatory these next couple of months prior to shipping to the launch site next summer.”