Jupiter’s satellite Ganymede is an intriguing place: It is the largest moon in the solar system, being bigger than Mercury, and unusually for a moon it has its own atmosphere and magnetic field. Tomorrow, June 7, the Jupiter exploration probe Juno will perform a flyby of the moon, providing the closest encounter with it in decades.

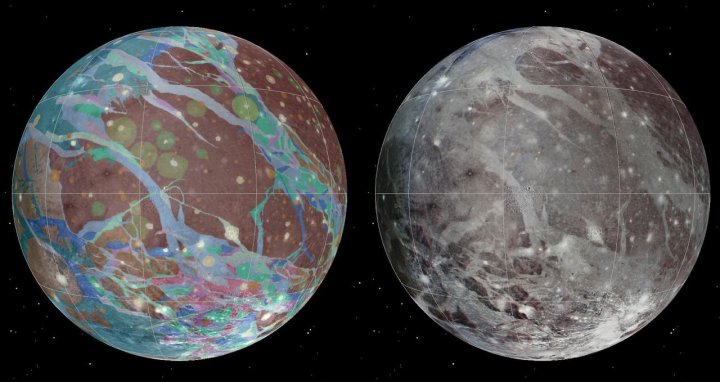

No mission has come this close to Ganymede in over 20 years, since the Galileo spacecraft made a final close approach in 2000. It was this mission that discovered the moon’s magnetic field and captured the data used to make the maps illustrated at the top of this page. More recently, the New Horizons probe passed by Ganymede on its way to Pluto, picking up some readings as it went by in 2007.

But to understand more about this intriguing place, we need to send more specific instruments there. That’s what Juno can offer, with its modern instruments like its Ultraviolet Spectrograph (UVS), Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM), and Microwave Radiometer’s (MWR).

“Juno carries a suite of sensitive instruments capable of seeing Ganymede in ways never before possible,” said Juno Principal Investigator Scott Bolton of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “By flying so close, we will bring the exploration of Ganymede into the 21st century, both complementing future missions with our unique sensors and helping prepare for the next generation of missions to the Jovian system – NASA’s Europa Clipper and ESA’s [European Space Agency’s] JUpiter ICy moons Explorer [JUICE] mission.”

Juno’s microwave radiometer instrument will be investigating the moon’s icy crust, which is thought to cover a saltwater ocean beneath.

“Ganymede’s ice shell has some light and dark regions, suggesting that some areas may be pure ice while other areas contain dirty ice,” said Bolton. “MWR will provide the first in-depth investigation of how the composition and structure of the ice varies with depth, leading to a better understanding of how the ice shell forms and the ongoing processes that resurface the ice over time.”

Juno’s cameras will get used as well, including the beloved JunoCam which has taken many stunning images of Jupiter. Even though it was intended to be an instrument for public outreach rather than for scientific use, the researchers think they can still use the images it collects to learn more about this moon.

The challenge is the Juno will pass by Ganymede very quickly, so the team will have to act fast to get the data they want.

“Things usually happen pretty quick in the world of flybys, and we have two back-to-back next week. So literally every second counts,” said Juno Mission Manager Matt Johnson of JPL. “On Monday, we are going to race past Ganymede at almost 12 miles per second (19 kilometers per second). Less than 24 hours later we’re performing our 33rd science pass of Jupiter — screaming low over the cloud tops, at about 36 miles per second (58 kilometers per second). It is going to be a wild ride.”