Microsoft doesn’t just make Windows and Surface tablets — it’s also doing some pretty interesting work with quantum computers. And, at least according to the Redmond, Washington-based company, it’s just made a notable advance in this domain.

Working with researchers from the University of Sydney in Australia, the Microsoft investigators say they have found a way to control thousands of qubits, the basic units of quantum information that are equivalent to binary bits in a classical computer, at extremely low temperatures.

This is important because one of the big challenges with quantum computers, which have the potential to change the face of computing as we know it, is something called qubit decoherence. This is the cause of many errors in quantum computing, and results from the environment interacting with qubits in a way that changes their quantum states.

“Each qubit needs to be controlled by a bunch of wires that typically run from racks of electronics at room temperature to the qubits at the end of a dilution refrigerator, at 0.01 degrees kelvin, [which is] close to absolute zero,” David Reilly, principal researcher and director of Microsoft Quantum Sydney, told Digital Trends. “Controlling qubits in this way taps out around 50 or so qubits. It simply doesn’t scale as an approach to controlling thousands of qubits and beyond. Running wires from racks of electronics resembles the first electronic computers of the 1940s rather than the integrated circuit chips we have today.”

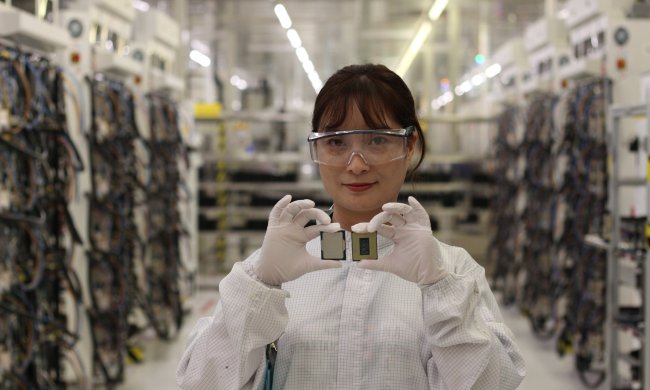

The researchers developed an innovative solution to this problem. It consists of a control chip they call Gooseberry, which enables the control system to scale, and alleviates the bottleneck of control wires and signals that otherwise exist. The control chip consumes only a tiny amount of power. This means that it does not heat up the qubits themselves.

“The chip is the most complex electronic system to operate at this temperature,” Reilly explained. “This is the first time a mixed-signal chip with 100,000 transistors has operated at 0.1 kelvin, [the equivalent to] -459.49-degrees Fahrenheit, or -273.05-degrees Celsius.”

Reilly said that this work represents a “big step” forward for quantum technology, although there are still “more leaps” that need to be made before a truly useful quantum computer can be developed. When it does, however, hopefully all of the research and development effort that got it to that point will be more than worth it.

A paper describing the work, titled A Cryogenic Interface for Controlling Many Qubits, was recently published in the journal Nature.