In space exploration, it pays to hope for the best but prepare for the worst. In that spirit, on Saturday SpaceX is testing out its Crew Dragon capsule, which will eventually ferry astronauts to the International Space Station, in a particularly dramatic demonstration of the capsule’s emergency systems: It will perform an “In-Flight Abort Test,” which involves blowing up a Falcon 9 rocket.

The abort test follows a successful static fire test this week, in which the Falcon 9 rocket first stage fired its main engines while staying on the ground. SpaceX confirmed the plans for the next test on its Twitter account, saying the test would “verify the spacecraft’s ability to carry astronauts to safety in the unlikely event of an emergency during ascent.”

Static fire of Falcon 9 complete – targeting January 18 for an in-flight demonstration of Crew Dragon’s launch escape system, which will verify the spacecraft’s ability to carry astronauts to safety in the unlikely event of an emergency during ascent

— SpaceX (@SpaceX) January 11, 2020

The aim of the test is to make sure that any astronauts who were onboard a capsule would be able to safely escape if something went wrong during a launch. The test this week will be unmanned, but it will check the same systems that would be used in the event of a manned mission needing to be evacuated.

The best way to test the capsule’s crew evacuation systems in the event of an explosion is to actually blow up a rocket for real. First, the Crew Dragon capsule will be attached to a Falcon 9 rocket as it would be in a real launch. Then the rocket will launch, and 90 seconds after liftoff engineers will shut down the rocket’s first stage engines and institute what is euphemistically referred to as a “rapid unscheduled disassembly” — also known as an explosion. Hopefully, the explosion will consume all remaining fuel in the rocket, so none falls into the ocean.

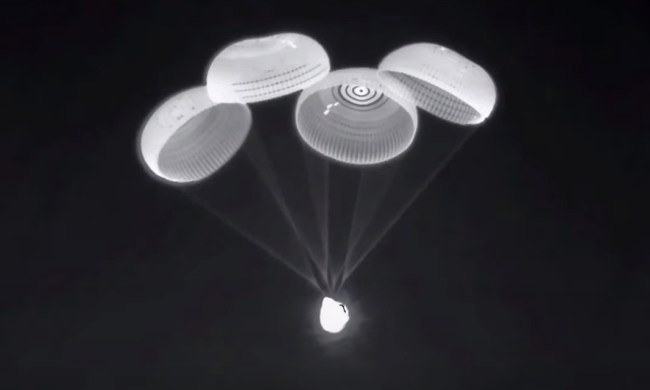

The Crew Dragon should be ejected away from the rocket by its thrusters which will fire for 10 seconds and move the capsule to a safe distance, from where it should deploy its parachutes and land safely in the Atlantic Ocean. Then the capsule can be collected for analysis to check it made its evacuation unharmed. SpaceX also says it will clear any floating debris from the ocean following the test as well.

The test is not only important for SpaceX, but also for NASA. In recent years, NASA has been pushing for greater involvement of private companies in space exploration and has set up partnerships with a variety of businesses including SpaceX. As part of its Commercial Crew Program, NASA aims to have private companies use capsules like the Crew Dragon to ferry astronauts to the International Space Station and back. The agency says that inviting private companies to commercialize parts of space will help lower costs and make further exploration more affordable.

However, the Commercial Crew Program has had its share of challenges and setbacks, with frequent delays and missed deadlines. In addition to SpaceX’s Crew Dragon, Boeing is also building a capsule for ferrying astronauts called the Starliner. The Starliner was supposed to be launched in May last year but this had to be delayed several times, and then there were problems with parachutes not deploying in another test. Finally, the orbital flight test went ahead in December but it didn’t go as planned — the capsule failed to make it to the ISS due to a problem with the automated systems’ timer which prevented the craft from achieving the correct orbit.

SpaceX’s Crew Dragon has fared somewhat better in its testing, with successful parachute tests and engine tests. However, a leaky valve caused a dramatic problem in a thruster test in April last year when a capsule exploded on the pad.

These problems have caused strain in the relationship between NASA and SpaceX, with NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine taking to Twitter in September last year to criticize SpaceX for focusing on its Starship spacecraft instead of the Crew Dragon. “Commercial Crew is years behind schedule,” Bridenstine wrote. “NASA expect to see the same level of enthusiasm focused on the investments of the American taxpayer [as is focused on the Starship]. It’s time to deliver.”

But in a joint press conference in October, the relationship between Bridenstine and SpaceX CEO Elon Musk seemed to be improved, with NASA positive about the potential of launching American astronauts from American soil for the since the retiring of the Space Shuttle program in 2011.

At the time, Musk spoke about the importance of testing and fortitude in the face of challenges: “You do tests if you think they might not be fine, and that’s why they’re called tests — so you can figure out what the issues are, improve the design, and retest,” he said.