I’m a lawyer. My client, Future Motion Inc., manufactures and sells the Onewheel self-balancing electric skateboard that debuted at CES 2015 to rave reviews, including from Digital Trends. But in December that year, just a month before CES 2016, the company learned that a Chinese company was planning to exhibit what appeared to be a copy, the “Surfing Electric Scooter.”

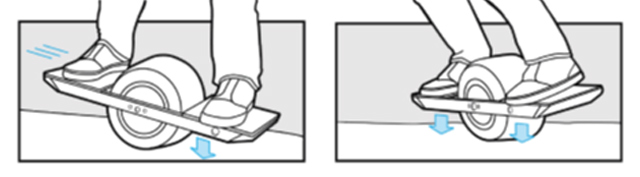

Even the images from the Chinese company’s instructions for use appeared to be ripped from Future Motion’s instruction manual, with a little extra color for good measure.

So we did something about it.

On January 7, 2016, I led a pair of United States Marshals onto the floor of CES, where we served court papers and seized the accused products and advertising materials, effectively shutting down the defendant’s booth. This not only stopped the exhibition of the knock-off, it also sent a strong message to other would-be copycats.

We had already tried to engage the Chinese company in a discussion. When that failed, we filed a complaint for patent infringement in U.S. federal court, along with a request for a temporary restraining order and a seizure order. Because Future Motion owned narrowly focused U.S. utility and design patents covering Onewheel, the motion was quickly granted — leading to a stunning and highly public seizure.

Unfortunately, the problem has only gotten worse since then.

The clone wars

“Imitation is the sincerest form of flattery,” according to a 19th century proverb. After investing in the development of an innovative new product, only to see cheap imitations quickly flood the market, a tech company might disagree.

Most companies are well aware of the possibility that cheap knockoffs will quickly follow the launch of a successful product or brand. In 2015, federal customs agencies reported seizing a combined 28,865 shipments containing products that infringed on intellectual property rights.

As manufacturers dispute their patent rights, low-quality knock-offs continue to capitalize on market demand.

The estimated retail value of the products seized – had they been legitimate – topped $1.35 billion. About half of the fake goods were traced to China, where a centralized manufacturing industry facilitates rapid replication of new technology. More than a third were traced to Hong Kong.

Add robust online shopping platforms that offer manufacturers direct access to consumers in the U.S. and around the world – such as Amazon, eBay, and Alibaba – and shoppers are greeted with a host of products that appear eerily alike, with the exception of the price tags. Legitimate brands generally maintain consistent pricing, and imitators typically undercut those prices significantly. Of course, the quality of the imitations is often as low as the price.

Apple recently filed suit against Mobile Star LLC, for allegedly selling counterfeit cables and power adapters on Amazon. Apple claims that the chargers and cables were labeled as genuine Apple products, but 90 percent of those purchased by Apple via Amazon proved to be counterfeit and – in the case of one review citing fire – dangerous. Unwitting consumers looking to save some cash may not be able to differentiate between the real and fake, putting their devices and even well-being at risk.

Battles over patent rights also have been breaking out in the hoverboard space, where celebrities embracing the high-tech personal transporters spurred a frenzy of demand only too eagerly filled by imitators. In one report from late 2015, the U.K.’s National Trading Standards Safety team in Scotland assessed 88 percent of 17,000 inspected hoverboards as unsafe, and stories of these devices bursting into flames were widespread.

Game of patents

Innovators of the original technology haven’t taken copycats lightly. Shane Chen of Inventist, Inc., who claims to be the original inventor of the Hovertrax-type hoverboard, holds a U.S. utility patent for a “two-wheel, self-balancing vehicle.” Last year he sued the Soibatian Corporation, which sold a similar product called the IO Hawk, for patent infringement. The two companies first collided at – wait for it — the 2015 CES show in Las Vegas.

Broader and more aspirational utility patents claim core aspects of a company’s technology.

It gets better. Ninebot (a Chinese company that acquired Segway) joined the fray later in 2015, alleging that it holds the underlying patents for personal self-balancing transporters. Ninebot eventually sued Hangzhou Chic, Inventist, and Inventist’s licensee Razor USA for patent infringement based on their sales of the IO Hawk and Hovertrax products. Meanwhile Inventist sued Ninebot for selling a unicycle-type self-balancing product. Both Inventist and Ninebot filed patent infringement complaints before the U.S. International Trade Commission, each hoping to bar foreign imports of Hovertrax-type products.

What’s a consumer to do? As manufacturers dispute their patent rights, low-quality knock-offs continue to capitalize on market demand. We just want our toys.

Can this imitation be stopped? Yes, but innovators need to do their part by obtaining intellectual property rights around their new products, and the government needs to help enforce those rights. As we saw when U.S. Federal Marshals carted off counterfeit Onewheel boards at CES 2015, companies that do it right hold powerful tools.

Protect your turf

To deter copycats and create enforcement options, including the possibility of a dramatic remedy like a trade-show seizure, companies need to secure the right intellectual property (IP) protection from the start.

Somewhat counterintuitively, narrowly tailored IP rights can be more effective to stop knockoffs than broader rights. Think trademark and copyright registrations, design patents, and sharply focused utility patents. They’re quick and relatively cheap to obtain, yet can have great enforcement potential against imitation products. In the case of Future Motion, its design patent and narrowly focused utility patent effectively illustrated the similarities of the two products and the potential for confusion in the eyes of consumers.

Broader and more aspirational utility patents claim core aspects of a company’s technology. They’re powerful tools for preserving the company’s maximum rights in an invention, and they can be used to deter more legitimate competition than just knockoffs. However, because of the greater complexity, broad patent protection can take longer to obtain and can be more difficult, time-consuming and expensive to enforce. Just ask Ninebot or Inventist.

And the battle never ends. Innovative companies need to continuously invest in expanding their rights. Despite only introducing its Onewheel product in early 2015, Future Motion has obtained three U.S. utility patents, two U.S. design patents, utility patents in China, Taiwan and Germany, and more than 20 trademark registrations in at least seven different countries. This portfolio of rights spans a wide scope of protection, allowing the company to continue deterring copycats.

By obtaining and aggressively enforcing an appropriate mix of intellectual property rights surrounding an innovative new product, companies can protect their investments and market positions.