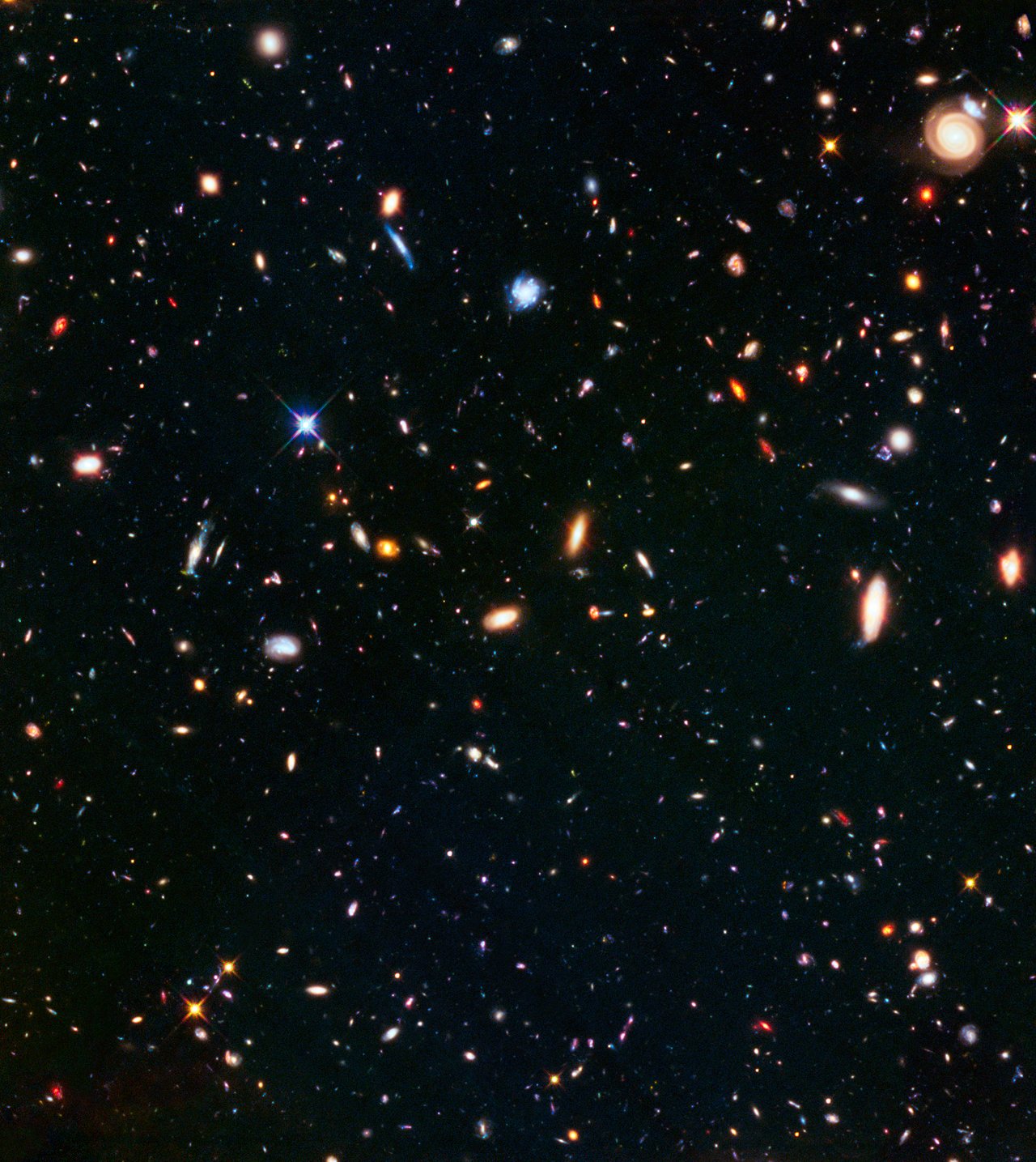

As part of a three-year, 840-orbit program, Hubble recently took photos of a cluster of star systems called Abell S1063, identifying 16 new galaxies. The images show galaxies that were previously too distant to photograph. While there was definitely a pretty powerful telescope involved, the reason the Hubble was able to see so far isn’t from new tech but a theory as old as Einstein, because, well, the theory actually stems from Einstein’s theory of general relativity.

First, a quick science lesson: Photography lenses and telescopes both work by using pieces of glass to bend light rays to focus them. But just like gravity pulls objects, it will also bend light. The effect is called gravitational lensing. On a large enough scale like a sizable chunk of the universe, gravitational lensing will pull light in enough to create a telescopic effect without an actual telescope.

The gravity from Abell S1063 bends the light so much that the Hubble was able to see galaxies behind it that current telescopes can’t yet reach. The images have led to the discovery of a galaxy that, because of how long it takes light to cover such a huge distance, appears to observers on earth like it did about a billion years after the Big Bang, according to NASA.

Abell S1063 isn’t the only cluster with enough mass to bend light either. Scientists have already observed three other clusters as part of the Hubble’s Frontier Fields program, with plans for viewing two more. Those earlier clusters allowed Hubble to photograph a supernova last year.

The Frontier Fields program involves collaboration from teams of researchers from around the world, including NASA and the ESA.