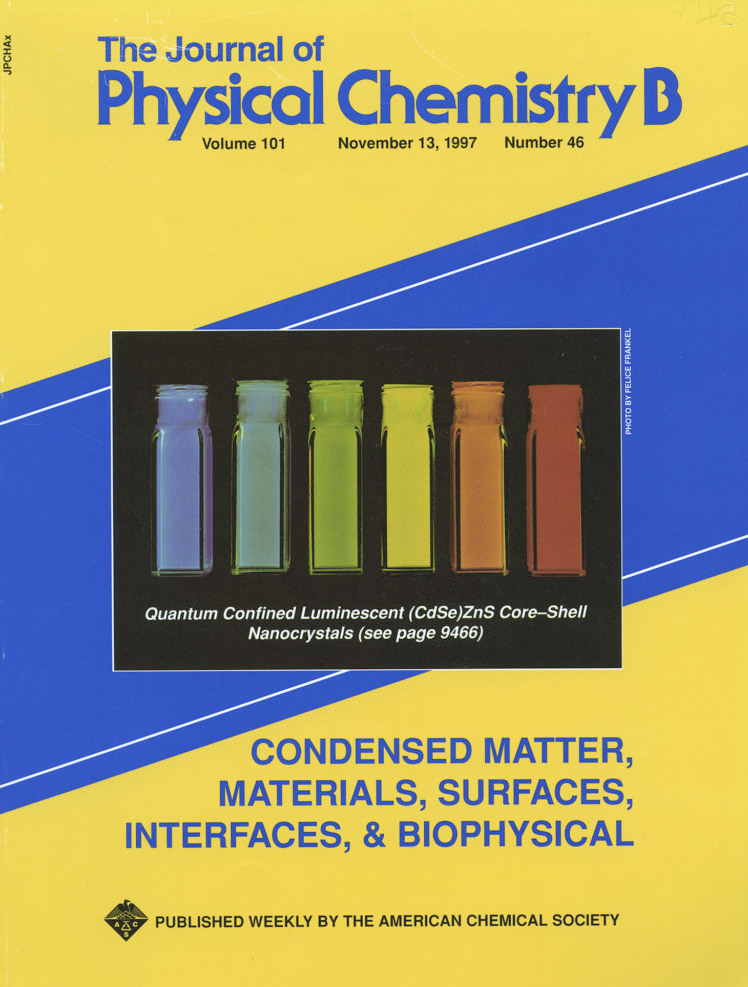

Felice Frankel is an educator, photographer, and research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Her passion for science started at a young age, eventually merging with her photographic experience and eye for design in a unique career as a science photographer. Since 1992, she has helped scientists better communicate their research and ideas through strong visual presentation, leading to the appearance of her work in numerous publications, including National Geographic, Scientific American, and Nature.

She has published several books, and her latest, Picturing Science and Engineering, is out December 11 from the MIT Press. It offers advice for scientists and photographers alike on how to better make science photographs for everything from presentations to magazine and journal covers.

Digital Trends recently spoke with Frankel via email about her new book, her career journey, and what it means to be a science photographer. The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

How did you get into science photography?

Even as a child, I remember paying attention to the world around me and wondered why things were the way they appeared. In my Brooklyn grammar school graduation booklet, I wrote “chemist” as a sixth-grader’s dream of what to become.

In college, my undergraduate days and evenings were filled with science courses. After graduating, I worked as a lab assistant in a cancer research lab at Columbia University.

In 1968, my husband sent me a Nikon camera to play with while he spent the year in Vietnam as a surgeon. That was the beginning of what initially started as an avocation.

The turning point in my professional life as a science photographer began during my mid-career Loeb fellowship, at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. The fellowship was given to me for my work as an architectural and landscape photographer.While my colleagues sat in on policy and design classes, I lived at the Science Center. I audited every science class I could fit into my schedule and listened to the brilliance of Stephen Jay Gould, E.O. Wilson, and Robert Nozick, among others.

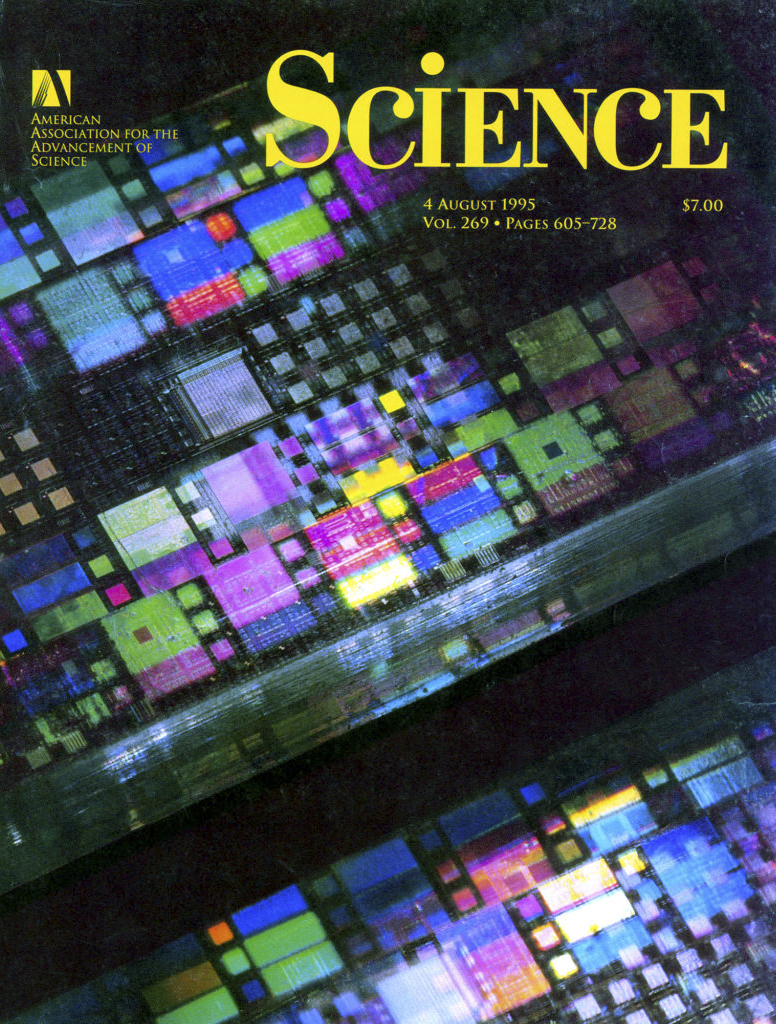

One of the other courses was given by a chemist who seemed “visual” in his presentations. I had no idea who he was, and after class one day, I approached him and invited myself to his lab to see what he was working on. Arriving at the lab, I introduced myself to Nick Abbott, one of the researchers working on a paper that was just accepted to Science Magazine. When I asked to see their images for the paper, I carefully suggested that I should [try photographing them], and I did.

We got the cover.

That Harvard chemist, George Whitesides, turned out to be world-renowned. He said to me, “Felice, stay with this. You are doing something that no one else is doing.” I did stay with it and I will forever be grateful to him for his encouragement and help in opening up doors for me.

In 1994, I happily landed at MIT and I have a held a position there since then.

“Science” is quite a broad term. What does it mean to be a science photographer? Do you focus on specific disciplines?

The challenge in fitting what I do into a neatly boxed category is difficult. I work in a host of areas: biology, chemistry, biomedical engineering, synthetic biology, physics, chemical engineering, mechanical engineering, material science, and engineering, and quite a number more. So to isolate one wouldn’t make sense.

We have rules about image manipulation in science.

What I am finding these days is that so many of the boundaries in various fields of science are breaking down and it’s even hard to slot the research into one category. The one area to which I definitely do not contribute is astronomy. They don’t need me.

But even in areas that are not photographable, like particle physics, I still find myself in fascinating conversations about how to depict that which cannot be seen. It’s a great deal of fun pushing these researchers into thinking about their use of color, for example, and more important, finding the right metaphor.

What are some of the key challenges in science photography that aren’t as common in general photography?

These days where mostly everyone considers themselves as a photographer, the image is “owned” by everyone and with that ownership comes an ease of image manipulation. It’s easy to “fix” an image if it’s not quite right. But in science, it’s critical to ensure that any manipulation to an image is carefully considered.

In fact, most of the time, it is not ethical to change an image. The image is the data and data cannot be manipulated in science research. We have rules about image manipulation in science, which I discuss in my book.

However, there are times when enhancing an image makes the science more communicative. Take, for example, many of the stunning Hubble [Space Telescope] images. Viewers think the universe really looks that way. Well, it turns out that most of those images are color-enhanced for communicative purposes. The ways in which images are manipulated is a subject not discussed enough.

Specific audiences — such as architects — have specific requirements for photography. What do scientists look for in images that a general audience might not?

The question is interesting because the answer has changed from when I first began in 1992. At that time, I found that very few researchers were interested in how communicative their images were, that is, whether the aesthetics of the image should play a role. In fact, many scientists were cynical about a compelling image or presentation. If a slide was well-designed, then the thinking was that the design might be hiding mediocre research.

I have always argued that I do not make art; my intention is not to be an artist.

That has changed. The present younger research community understands the power of a compelling presentation. And it’s not just about making the pictures “pretty.” It’s about making pictures that communicate big ideas in research, science, or data in a visually pleasing way. The aesthetics, if handled properly, helps the viewer see what you want them to see.

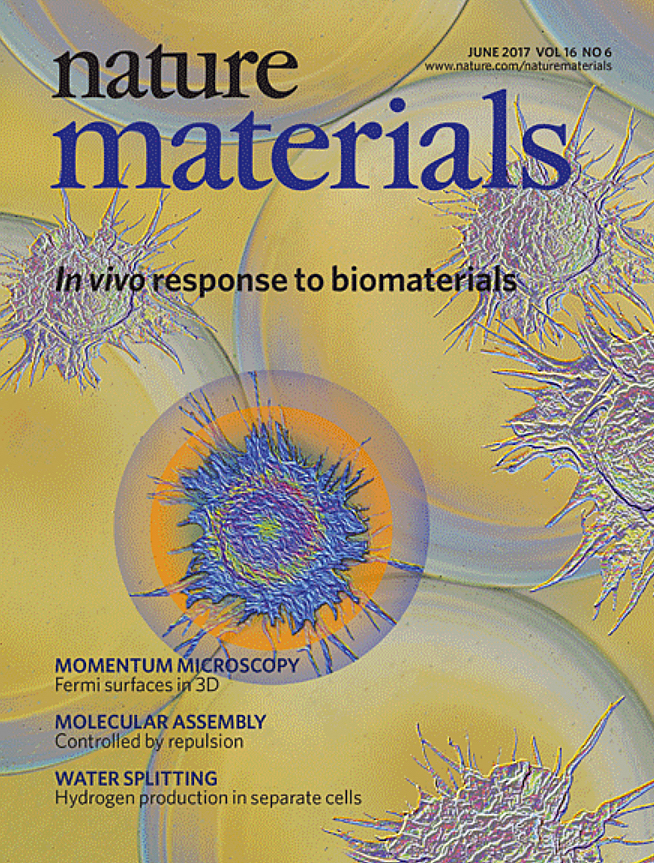

Lately I am observing that some of the most important journals are changing the perpetuated, sometimes difficult to comprehend standard approach to graphics. But here again, in addressing the issue of manipulation, we must question how far can we go if we manipulate our final image. Unlike the rest of the photographic world, if an image has been enhanced, we have to say exactly what was done to that image. Period.

So you would say the artistic side of photography — composition, lighting, etc. — is important in science photography?

I am not convinced that “composition, lighting, etc.” should be described as artistic. Using those tools is a means to clarifying and communicating exactly what the science image is about. I’d prefer to call them design tools.

I have always argued that I do not make art; my intention is not to be an artist. I am more of a visual journalist, perhaps. I design images to communicate a concept.

What gear do you shoot with? Are there any specialized, DIY, or otherwise unique tools that you use?

I have stayed with my Nikon cameras, but they are now digital. I mostly use a 105mm macro lens. I also attach the cameras to my two optical microscopes; an old Wild stereo microscope and a compound Olympus scope. The latter has special filters and objective lenses that give me the ability to use a certain technique in microscopy: Nomarski interference contrast.

[Read our review of Nikon’s newest camera, the mirrorless, full-frame Z7.]

When the material calls for a scanning electron microscope (SEM), I use the one on campus, but always with help from someone who knows more than I. My phone is giving me some pretty amazing images lately, but there are challenges which I describe in my book.

The more recent addition to my equipment is an Epson flatbed scanner, with both transmitted and reflective light sources. I have a whole chapter devoted to the use of the scanner and describe how to make some amazing photographs. And, it is hard to underemphasize the importance of lights of many forms, sizes, and qualities. In my book, I urge the readers to discover their own light. It’s important not to become formulaic in your photography and to try all sorts of possibilities.

Your book, Picturing Science and Engineering, serves as a photography manual for scientists — but what about the other way around? Is there a market for photographers to find work photographing science?

I am convinced there is a market for photographers in science. The book is also intended for those interested in pursuing a career in science photography. An important component for those interested is to have a curiosity about what they are seeing. The conversations I have with the researchers, before I even set up the camera, are critical. I simply have to understand the essential pieces of the research, so it is important to ask a ton of questions. I am not embarrassed if I don’t understand the basic concepts. I just delve as deeply as I can.

So far I’ve been lucky. MIT researchers love explaining things.

Sports photographers have the Olympics, wildlife photographers have that rare bird or deep sea fish, and portrait photographers have their favorite celebrity. What’s on the bucket list for a science photographer?

My answer is simple: If I can nudge someone outside the research community to want to look at the science I am showing, to make it accessible enough so that they want to ask a question, then I have done well.