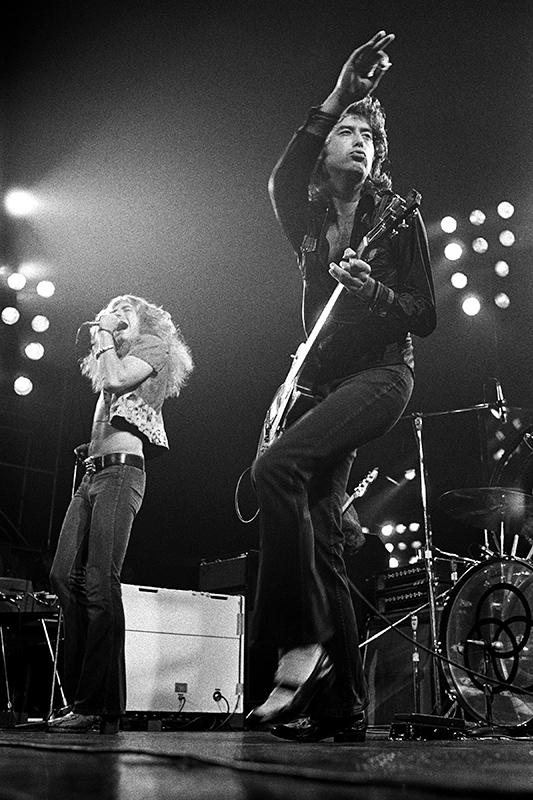

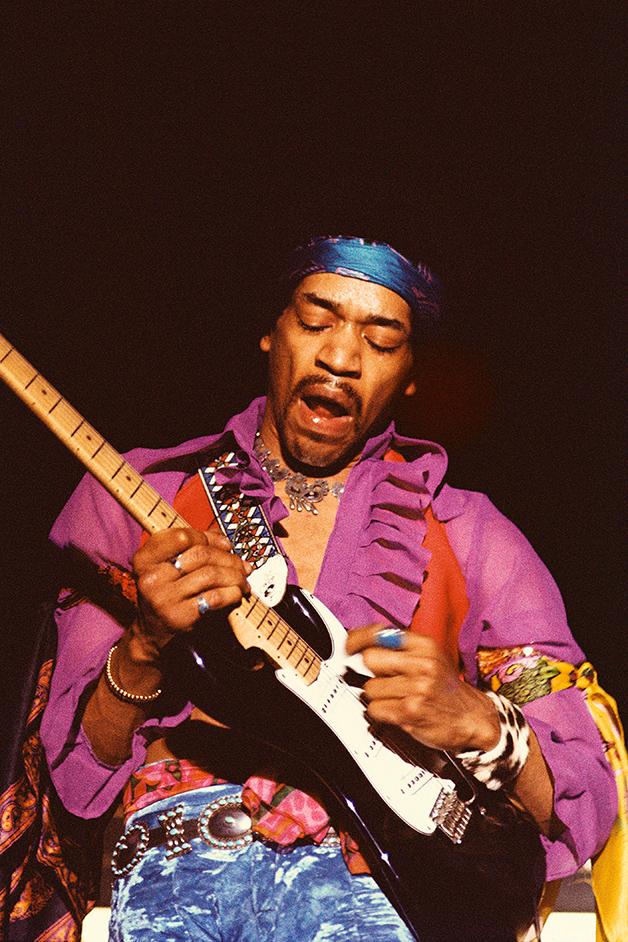

Photographer Robert Knight is almost as much of a legend in the business at this point as his rock star subjects. He is known for being one of the first photographers to shoot the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Led Zeppelin, as well as holding the less-than-pleasant distinction of being the last photographer to shoot Stevie Ray Vaughan. And his almost uncanny ability to predict (and photograph) the next big guitarists was the subject of the 2009 documentary Rock Prophecies.

“Back in those days, in order to be a photographer, you had to know what you were doing.”

While Knight still regularly takes the stage to shoot the rock gods, the latter has become his passion project, through which he looks for, discovers, films, and interviews the next generation of guitar heroes between the ages of 12-20, all over the world. We talked with Knight to discuss everything from shooting the icons to becoming a tastemaker, in the truest sense of the word.

Do you still remember the first concert you shot?

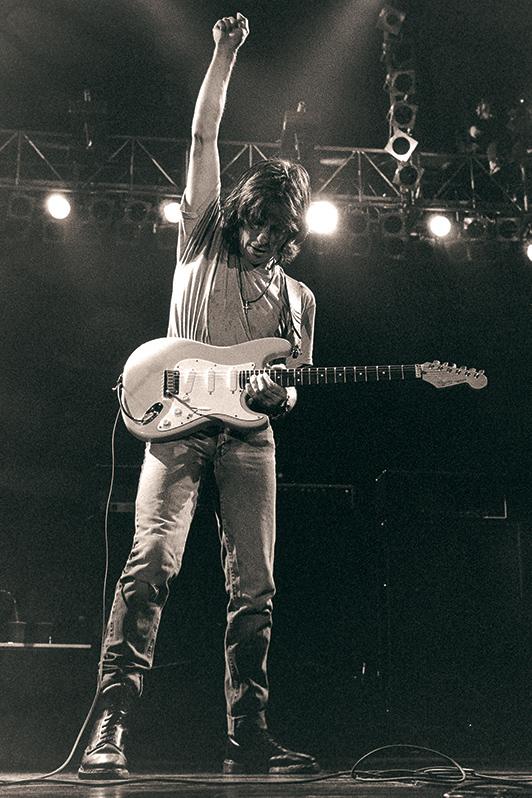

Jeff Beck, with Rod Stewart. 1968. And within a month, I had shot Hendrix and Santana, Jethro Tull. It was amazing. All those guys came rolling through the Fillmore [in San Francisco]. It’s astonishing what my first six months as a photographer was.

What was going so right for you at that time? What were the keys to your success when you were first starting?

I think what was going right for me was that I knew what was going to happen in music before other people. Back in those days, in order to be a photographer, you had to know what you were doing. Today, you don’t. You don’t need to know anything. If I had my Nikon D3 or D4 back in 1968 with Jimi Hendrix, imagine the pictures I would have. Back then, film was expensive, and I would only shoot one or two rolls. Nobody would push film in those days. If you’ve got 1/8 of a stop or 1/4 stop latitude, you had to get it right. But with film, there was no playback on the spot. You had to wait sometimes two to three days before you knew whether you got it. That’s what photography was. So there weren’t people there with cameras. Now I go to venues and there are 60 people in the pit, some of whom are holding an iPad, filming concerts with iPads. I’m stunned.

With that sea of cameras, what do you do nowadays to stand out?

I get a lot of young photographers going, “I want to do what you do. I want your job. Can I shoot The Rolling Stones?” Of course you’re not going to shoot The Rolling Stones, because access to these kinds of bands now is very limited, because they’ll hire one guy, they’ll own the pictures, and then they make all of the money. My advice to you is, find a band, like I did with Led Zeppelin, who is young and no one knows, help them and ride the rocket ship with them. I keep doing that, year after year, over and over and over. I will help young bands, not charging them, ingratiating myself, and then riding it back up with them. It keeps me fresh. But now, to differentiate myself when Journey or Aerosmith or Def Leppard call, and they want us to come on the road and shoot, I won’t shoot in the pit anymore. I want to be on stage, wandering around during the show, shooting onstage with the band. That’s what I do, and they let me do it. Of course, we get shots that the guys in the pit don’t get.

What type of equipment are you using when you shoot live?

I love my Nikon D3. I start at 3,200, sometimes go to 6,400 [ISO], and everything I shoot is on that. I try to work with two lenses, a 24-70 [millimeter] and then the 70-200, and put myself in a position where I don’t have to carry nine cameras and all these bags of lenses. I’m pretty fluid on the stage.

How did the Brotherhood of the Guitar come about?

[Rock Prophecies] was very successful and it resonated with people for many different reasons. But in there, a young director challenged me and said, “Listen, you were the first guy to work with Led Zeppelin in America, and you’ve always discovered bands before anyone else. Can you still do this? Can you find some artists we can film, and by the time the movie comes out, perhaps they’ll be somewhere?” So I found a band in Australia called Sick Puppies, convinced them to move to America. Within a year, they were on Jay Leno. They’ve had three albums and 12 Top 40 records since. And I found a 15-year-old boy in Honey Grove, Texas, who is 35 minutes of a 90-minute movie – sort of a backbone story in which I helped him and he ended up getting signed and touring two tours with Jeff Beck. It just really worked out. Once the movie came out, we were in heavy rotation on PBS and Netflix, and I got inundated with these tips from all over the world saying, “Help me like you helped that boy.” I went to Fender and Guitar Center and Ernie Ball and some other people who were my clients and friends and said, “Listen, there’s an opportunity here that you’re missing, because all of the guitar heroes that you’re presenting to kids are 70 years old. And they’re not interested, nor do they know who they are. And the guitar is going to go the way of the accordion or the saxophone if a new generation of kids doesn’t embrace it.” Right now, it’s a very unfavorable instrument because it takes too long to learn. You could go to Guitar Center and buy a beatbox and some electronic stuff and make music tonight. So the idea was to create new role models.

Do you ever see yourself stopping, either shooting or working with the Brotherhood, or are these things you want to keep doing as long as you can?

Because I’m moving into the world of these young kids, and I’m passionate about them not getting ripped off, I’m also getting involved in the management side of it. I will always be a photographer; I’ll never stop taking pictures. But I could see myself rolling back to 50 percent of my time doing photography and 50 percent in direct management. And then the 50 percent photography I am doing is really meat-on-the-bones bands. If Jeff Beck came, I’d run. I’d still get up on the stage and keep up with him. But I’m really fascinated in trying to make a difference in the music business, because I’ve watched and know everybody. I literally know the presidents of record labels and management companies, because I’ve worked with them for 46 years. I do manage a couple artists. One is this 22-year-old kid who plays with Shania Twain. He’s probably one of the highest paid young guitar players in the world. We’re doing great things with him…when I hit 100 [participants in the Brotherhood], it’s going to be a lot harder to get in. And then I’m going to put kids between 13-16 in charge of it. They’re going to decide who gets in. Because what you’re doing is teaching younger people to think in a business sense, to make decisions based on business and not art; a function of a party; or the sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll part of it.