Make sure to check out our full Lytro Camera review.

We’ve only just been introduced to Lytro, and already it’s been labeled the next revolution of digital photography, a surprising label given how little we know about it. In truth, light field or plenoptic cameras have been an industry project for years, and only now are consumers getting a look at their potential. While just a taste of this technology has been enough to whet the general public’s light field interest, there are a few things to consider before labeling Lytro a sure thing.

Light field technology

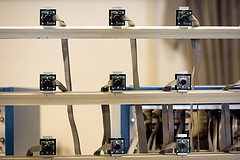

First, a quick background on Lytro’s technology. While the term “light field” has been around since the 1930s, we’ve only seen it applied in a handful of ways within recent years. The infamous bullet scene in The Matrix (as well as other effects from the movies) were filmed using an arc of multiple cameras. But putting this type of technology into a consumer-friendly device surfaced around 2005 – or at least the idea did. Ren Ng introduced a prototype “light field camera” that improved upon a plenoptic camera (the more technical name for the device) developed by MIT in the 1990s. Six years ago, though, it was little more than a concept – albeit a very intriguing one. Ng wrote a paper with several colleagues discussing how to package this technology in a point-and-shoot camera, in which they write they take heavy inspiration from the work of Edward H. Adelson and John Y.A. Wang. Adelson and Wang published a paper in 1992 devising how to create a camera that would analyze the optical structure to infer objects’ depths. However, Ng and co. used fewer lenses in their prototype, as well as focusing on…well, the refocusing bit, all of which is thoroughly explained in Ng’s award-winning dissertation.

So in short, this is how it works: The camera has multiple small lenses, in addition to the traditional digital camera lens and the sensor. These lenses mean a device can capture more light from a much larger range of directions. By being able to collect more, these types of cameras have more capabilities than traditional ones do – i.e., the refocusing after a shot has been taken, crisp images, and 3D function.

Questions and answers

There are a few very basic questions surrounding Lytro. Up to this point, all we’ve seen are images (presumably) taken with Lytro. We’ve been told it will be handheld. That’s about it. What is this camera going to look and feel like? Given its revolutionary take on the image processor and very different inner hardware setup, it could look like something we’ve never seen before. Will it fit in a pocket? Will it need a neck strap? Wrist strap? Will there be an entire lineup of different models, ranging from point-and-shoots to pocket camcorders to DSLRs? One photographer who was able to test out a prototype told the New York Times the model he used was the size of an average point-and-shoot and the image quality was similar to that of a Canon or Nikon pocket cam.

All skepticism about the unknown aside, there are a few concrete things we know Lytro will come equipped with. What’s become known as its “focus later” technology, giving users the ability to change focus between the foreground and background. But what is interesting is that this focus-and-refocuses capability doesn’t require a software download of any kind. Anyone will be able to click and play. Will Lytro be able to save a photo that’s just entirely blurry? We don’t know if it’s that much of a catch-all. Maybe more interesting for experienced photographers is Lytro’s shutter lag, or lack thereof. The camera doesn’t focus before a photo is taken, meaning shutter lag is an impossibility.

Lytro’s construction also means it works exceptionally well in low-light settings. Which makes sense: The camera captures far more light than your average model. The team behind Lytro says a flash isn’t even necessary.

Challenges

What Lytro has done for photography is comparable to what digital cameras did – obviously not as groundbreaking, but this isn’t some trendy photo editor that’s going to be forgotten within a year’s time. This technology could change the industry in general; it wouldn’t be surprising to see many manufacturers begin to research creating a light field camera of their own. But Lytro isn’t here just to introduce an idea: It wants to sell that idea for a profit. The company isn’t licensing its technology to camera makers, although Ng commented on this saying “Never say never.” Ng also says “we can do it better.” It’s important not to forget that Lytro isn’t the only company who wanting to introduce this type of thing to a wider

No matter how confidently Ng and the Lytro team will take on legacy camera makers, they will face the same big challenge: Camera phones. The iPhone is the top “camera” on Flickr, and the popularity and success of smartphone photo-sharing platforms is astounding. Which is why it would seem easier for Lytro to license its technology for camera phone makers and see the technology put there, where it would be welcome with opened arms and guaranteed success. It will be more difficult to go the traditional route and create a new lineup, but there’s something for the photo enthusiast to admire about that. The cameras will be manufactured in Taiwan and mainly marketed online, including via Facebook.

Heading toward a niche market?

So where does something like the Lytro camera fit in? While we can’t say for sure how much this thing will cost, we’re inclined to assume it will be pricier than your average point-and-shoot. A steep price could isolate some of its most interested parties: Entry-level consumers. “Like most ‘latest and greatest’ technology, I think harnessing the light field camera tech into something the average consumer can afford will be quite a feat,” William Chambers of Steve’s Digicams agrees.

While the technology behind Lytro is innovative and remarkable to say the least, we’re uncertain how it will play out with photo experts. We imagine that just about everyone wants to get their hands on a Lytro to give it a shot, but the interest lies more in the editing software and refocusing ability than in the camera itself (at least thus far). And there are legions of devoted photography enthusiasts out there who will balk at the idea of camera shortcuts. Lytro is amazing, but it’s still a shortcut. It basically eliminates having to know anything about depth of field.

For this reason, it isn’t difficult to imagine that there will be a decent amount of interest from amateur digital photographers, but if they can’t afford the camera, it might not make as big of a splash as it possibly could. Couple this with the fact that Lytro is working on a Facebook app and using the social network to create buzz, and it might be centering on a certain demographic. “If it can be produced in a affordable manner, I think the Lytro could revolutionize how the majority of consumers capture and share photos. I can see it now – everyone on Facebook and Twitter sharing photos that allow you, the viewer, to change the focal point with the click of a mouse,” Chambers adds. It really seems like this all gives viewers a more active role in imaging, and photographers a more passive one. And depending on which side you most align with could impact how you see Lytro.

But none of this takes away from the impression Lytro has made, regardless of whether you see it as a cheap workaround that denigrates the art of photography or a considerable leap forward in photo manipulation technology (or maybe just something you’re looking forward to using on your Facebook photos). Even if its cameras are a flop and seen as a gimmick, the software behind them won’t be.

Lytro Gallery

To try out Lytro’s focus-shifting capabilities, just click where you want to focus on the images below: