Try to remember a line from the last book you read. Or, if you’re not a big reader, the face of the last new person you met.

Now try to remember your significant other’s last Facebook status update.

According to a new study published in the journal Memory & Cognition, our brains may be more adequately wired to remember status updates and tweets rather than snippets from novels or faces. Subjects in the study were one and a half times more likely to remember posts than sentences from a novel and almost two and a half times more likely than to remember faces.

The natural skeptic would say of course we can remember online posts better. They have a more familiar context than, say, All Quiet on the Western Front. After all, the posts were probably authored by someone we know pretty closely and have a good chance of discussing a topic of keen interest to us. The researchers thought of that.

This article from Science Daily goes into some better detail about the experiments performed for the study. All of the updates and tweets used in the study were stripped of context and images. They were just random text.

The researchers’ theory is that online posts are written in a format that makes them more digestible by our evolutionary brain. They tend to use more colloquial speech and be more action-oriented.

Think about it. Out of the roughly 50,000 years of human history, only the last 5,000 or so have been spent using serious long-form writing. In the previous 45,000 years, our ancestors communicated mostly by short snippets of speech as they passed by each other. Writing was invented simply to keep those snippets straight. In other words, there isn’t much difference between “We saw a herd of buffalo going toward the river yesterday,” and “Katy Perry’s Grammy dress was ridiculous!”

The amazing thing is that it seems our language has come full circle, and only in the matter of an evolutionary blink of the eye. Although we have been writing, generally speaking, for about half of human history, most of those scrawlings on caves and pyramids were short, action-based reports about the day’s events. Sound familiar?

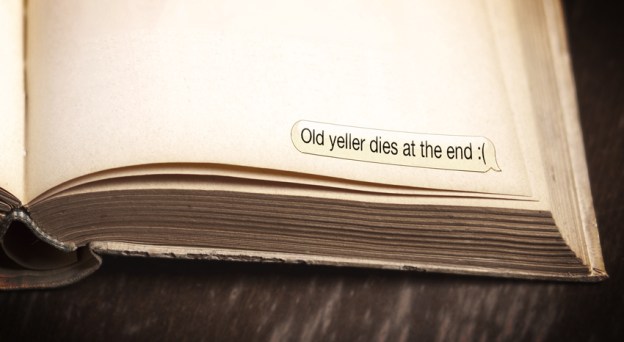

For all of its banality, we seem to be better suited to online writing. It’s bringing us back to our roots. But what does this new understanding do for our language moving forward? Is the novel dead? Will our language be reduced to a series of tweets in an Idiocracy-like future?

First off, the novel is not dead. Overall, the book industry is growing, thanks to our modern technology. Furthermore, it seems that fiction, in particular, is beneficial to our cognitive abilities. The brain – chemically and electrically – cannot distinguish from situations it reads about and situations it actually experiences. Therefore, reading fiction gives us a form of practice that we need in our every day situations. Reading long works can obviously increase long-term memory skills as well.

What this research shows is a better way forward for people seeking an improved way to generally communicate. One of the reasons online posts stick more in the human brain is because of their general informality. Just as we seek out friendly ears, we also seek friendly tongues.

Remember back to high school or college. Were you more likely to retain the information from a lecture delivered by the starched professorial teacher or – for lack of a better term – the “cooler” teacher? That is a lesson that can be used anytime you’re looking to get a point across.

The second point from the study was that online posts tend to be about an actionable event. In other words, get to the point. We bemoan our dwindling attention spans and how we cannot seem to stay focused on one thing longer than 30 seconds, but if you extend the results of the study a little bit, that seems to be another byproduct of our evolution. Our ancestors found it was simply too dangerous to stay focused for a long period of time, lest they miss the predator sneaking up behind them.

We adopted the art of long storytelling, either orally or through writing, in a need to be entertained. Once we had mastered our surroundings to a point where we had some downtime, we got bored.

The pessimists among us will point to our online world as the death of that enlightenment we worked so hard to achieve. There is still room in our language for both Twitter and high literature. As in most things in life, the secret is in balance.