As well as pulling in anything which comes to close to them, black holes can occasionally expel matter at very high speeds. When clouds of dust and gas approach the event horizon of a black hole, some of it will fall inward, but some can be redirected outward in highly energetic bursts, resulting in dramatic jets of matter that shoot out at speeds approaching the speed of light. The jets can spread for thousands of light-years, with one jet emerging from each of the black hole’s poles in a phenomenon thought to be related to the black hole’s spin.

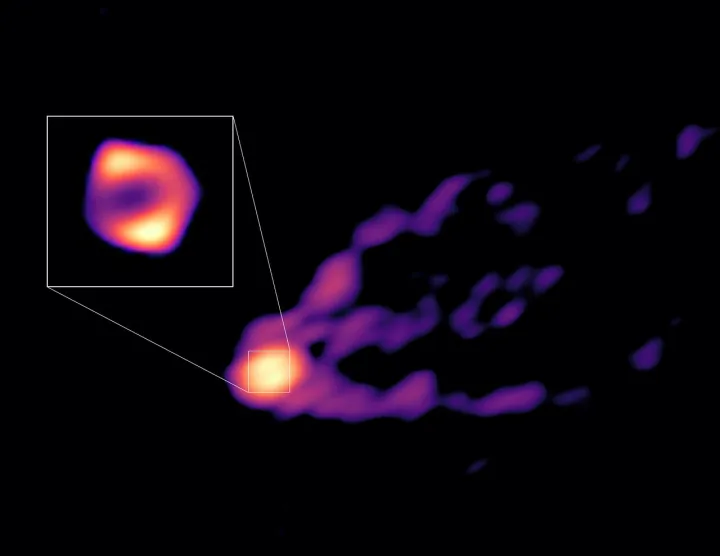

Some of the biggest jets in the known universe come from the huge black holes at the center of galaxies, called supermassive black holes. And now, for the first time, astronomers have imaged a supermassive black hole expelling one such jet. The black hole in question is the famous one at the heart of galaxy Messier 87, which is known for being the first black hole ever imaged by a collaboration called the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT). Using a similar partnership of telescopes around the world, astronomers were able to capture this monster black hole spewing out matter in a jet.

The observations have given a new view of the black hole itself too. “The original EHT imaging revealed only a portion of the accretion disk surrounding the center of the black hole. By changing the observing wavelengths from 1.3 millimeters to 3.5 millimeters, we can see more of the accretion disk, and now the jet, at the same time,” said one of the researchers, Toney Minter, in a statement. “This revealed that the ring around the black hole is 50% larger than we previously believed.”

The observations were taken with radio telescopes, including powerful arrays like the Global mm-VLBI Array (GMVA) and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), which use many smaller dishes working together to look at very distant radio sources. By combining the efforts of different observatories, astronomers could get a better look at this famous black hole. They knew the black hole was giving off jets, but they didn’t know exactly how or where those jets were forming.

“These results showed — for the first time — where the jet is being formed. Prior to this, there were two theories about where they might come from,” said Minter. “But this observation actually showed that the energy from the magnetic fields and the winds are working together.”

This helps scientists understand the process through which the jets are created, which involves the magnetic fields around the core of the black hole and the winds that blow through the disk of matter around the black hole, called the accretion disk. To learn more about this process, the researchers want to perform more observations using the global telescope network.

“We plan to observe the region around the black hole at the center of M87 at different radio wavelengths to further study the emission of the jet,” said Eduardo Ros from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in another statement. “The coming years will be exciting, as we will be able to learn more about what happens near one of the most mysterious regions in the universe.”