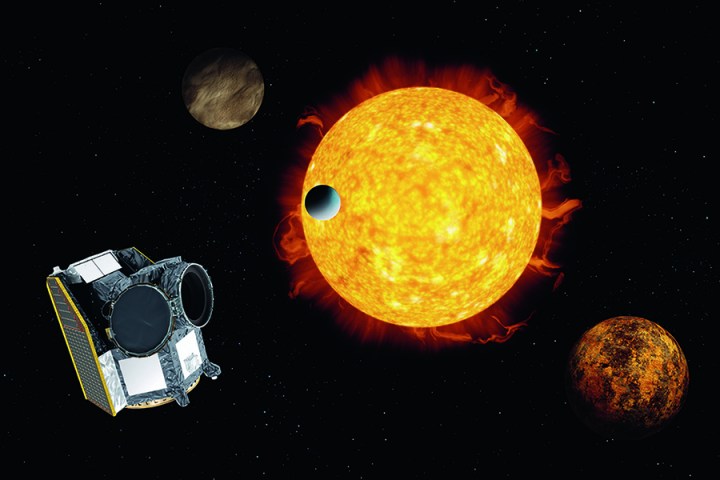

This week marks the one-year anniversary of the launch of CHEOPS, the European Space Agency’s exoplanet investigation satellite. CHEOPS looks at known exoplanets discovered by other missions and probes them in more detail, uncovering new information about these distant worlds. Here’s what it discovered in its first year:

Blurry stars

The first image taken by CHEOPS in February this year was not in fact of a planet, but a star — HD 70843, located 150 light-years away. The telescope took a deliberately blurry picture of this particularly bright star to check its brightness was properly detected, and all boded well.

CHEOPS also imaged another star, HD 88111, which doesn’t host any known exoplanets, but was useful as a test. That’s because CHEOPS detect exoplanets by looking at stars and waiting for planets to pass in front of them, in an event called a transit. By observing the star dimming by a tiny amount, scientists can infer the presence of an exoplanet and calculate properties like its size and orbital period.

A wispy puff

With the instruments confirmed to be working well, CHEOPS detected its first exoplanet in April this year. It looked to the star HD 93396, located 320 light-years away, around which orbits a planet called KELT-11b. KELT-11b is a large gas giant, being about a third larger than Jupiter but only one-fifth of its mass. That makes it one of the “puffiest planets” discovered so far.

CHEOPS was able to observe an eight-hour-long transit of the planet and to detect its size more accurately than any instrument before, pinning its diameter down to 181,600 km with an uncertainty of just 4,300 km.

Scorchingly hot

In September this year, CHEOPS investigated a “hot Jupiter” called WASP-189 b, which turned out to be one of the most extreme planets ever found. It sits so close to its star that a year there lasts just 2.7 days, with its orbit being twenty times closer to the star than Earth is to the sun. Not only that, but its host star, WASP-189, is 2,000 degrees hotter than the sun, which so incredibly hot that it appears to glow blue.

That makes WASP-189 b one of the few known planets to orbit a star this hot and this bright. The researchers estimate that the temperatures on the planet would be a scorching 3,200 degrees Celsius, which is hot enough to not only melt metals but also to turn them into gas. It also orbits at an unusual inclination, passing over the star’s poles rather than its equator.

A dramatic dodge

CHEOPS also had a close call in October this year, when it had to evade a piece of space debris. If the debris had collided with the satellite it could have destroyed it entirely, according to Willy Benz, head of the CHEOPS consortium. Fortunately, CHEOPS was able to maneuver out of the way and avoid the incoming debris.

With this exciting first year under its belt, CHEOPS will move on to studying hundreds of known exoplanets in the next few years, gathering more accurate information about them and learning new things about these strange, distant worlds.