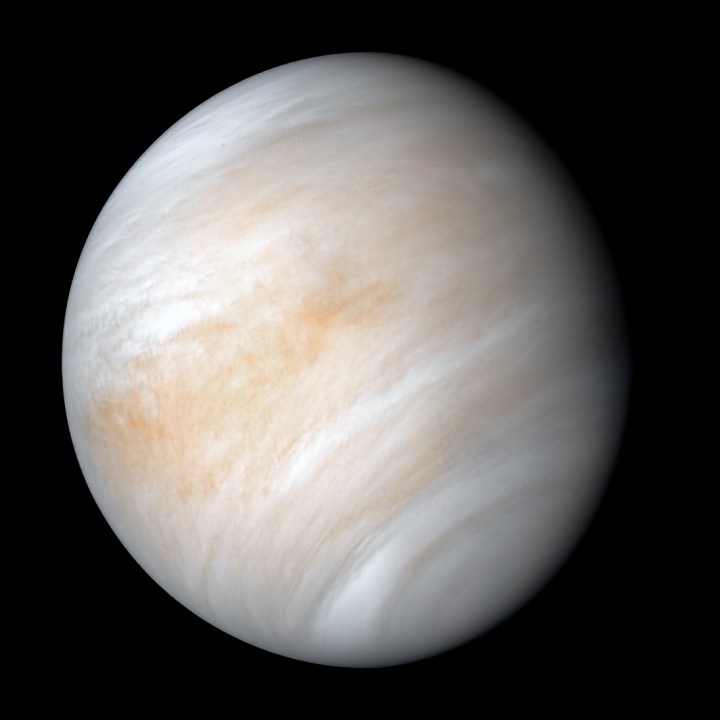

As Venus is right next door to Earth, you might assume that we know all about our neighbor in the solar system. But in fact, there’s much we don’t know about this planet, due to factors like the thick layer of sulfuric acid clouds which hide most of its surface. And there are some seemingly basic questions about the planet that we don’t have answers to — including exactly how long a Venusian day is.

Now, researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles finally have an answer to that puzzle, after 15 years of painstaking observations. They used radar to bounce signals off the planet’s surface and were able to work out not only the length of its days but also to learn about the size of its core and the axis at which it is tilted.

“Venus is our sister planet, and yet these fundamental properties have remained unknown,” said Jean-Luc Margot, a UCLA professor of Earth, planetary and space sciences who led the research, in a statement.

A day on our sister planet lasts 243.0226 Earth days, which is around two-thirds of an Earth year. Venus rotates extremely slowly, which is why its days last so long, and it also spins in the opposite direction to Earth and most other planets. More than this, the rate at which it rotates actually changes over time, with variation in the length of a day of up to 20 minutes. This has made it difficult to find an accurate figure for the length of its days.

“That probably explains why previous estimates didn’t agree with one another,” Margot said.

The researchers think that Venus’s strange, thick atmosphere might be responsible for this variation. Its atmosphere rotates much faster than the planet does, which might affect the rotation through momentum.

The team also discovered that Venus is tilted by 2.6392 degrees and that its core is around 2,200 miles across, which makes it a similar size to Earth’s core. The researchers made these discoveries by firing radio waves at the planet and watching for when the waves bounced back and the echo could be detected by telescopes on Earth.

“We use Venus as a giant disco ball,” said Margot. “We illuminate it with an extremely powerful flashlight—about 100,000 times brighter than your typical flashlight. And if we track the reflections from the disco ball, we can infer properties about the spin [state].”

The research is published in the journal Nature Astronomy.