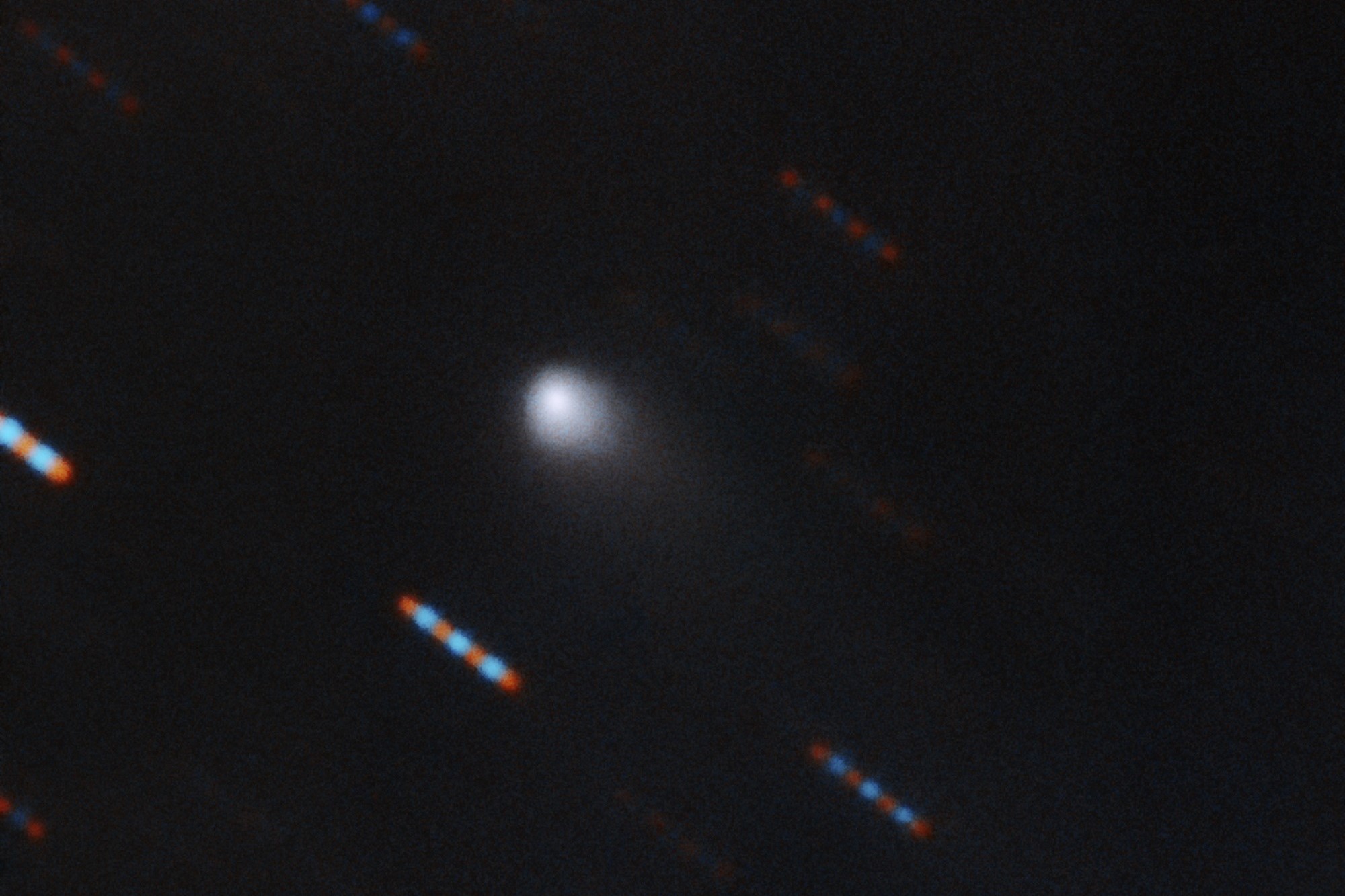

In September an interstellar visitor was discovered in our solar system — the comet 2I/Borisov, which was imaged by astronomers as it approached the sun. Now, a new study has looked in depth at what the comet is made of.

The small body is called a “planetesimal” by astronomers because it has the potential to become a planet under the right gravitational conditions. Most planetesimals in our solar system are icy, like comets, but a small fraction of them are rocky. But there should be planetesimals observable from outside the solar system too, the authors said in the paper: “Assuming that similar [planet formation] processes have taken place elsewhere in the galaxy, a large number of planetesimals are wandering through interstellar space, some eventually crossing the solar system.”

Scientists aren’t sure whether other solar systems are the same as ours in terms of the ways which planets are configured. Studying interstellar objects like 2I/Borisov gives us the chance to see how planets are formed in other areas of the galaxy.

The first chance to study this issue came with the discovery of the ‘Oumuamua interstellar object, which captured the public’s imagination when it was spotted in our solar system last year. Its color and brightness suggested it was made of rock and metals and had no water or ice, but scientists were never able to determine what exactly it was made of.

With the new object 2I/Borisov, scientists were able to perform a spectroscopy analysis and find out which gases were present in the comet’s coma, or the ball of particles and gases around the center of the comet. This was difficult as the object is close to the sun, so the glare from sunlight makes it tricky to gather enough light from the object to perform an analysis. It took two tries, but the scientists were eventually able to gather data from the interstellar visitor.

They saw a distinct spike in the ultraviolet spectrum which corresponds to cyanogen gas, a combination of carbon and nitrogen. This gas is found in comets in our solar system too, so it’s not unexpected. However, there is an interesting note about the gas: it is given off as the object approaches the sun and is heated, causing gases to evaporate.

That means that as the object approaches the sun, it may give off more gases which could give clues to its makeup. It will make its closest pass to the sun in December, so watch for more information about our interstellar visitor then.

The research paper is available to view on pre-publication archive arXiv and will be published in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters.