Researchers using the James Webb Space Telescope have detected carbon dioxide in an exoplanet atmosphere for the first time, demonstrating how using the new space telescope will help us to learn about far-off planets and even to find potentially habitable planets outside our solar system.

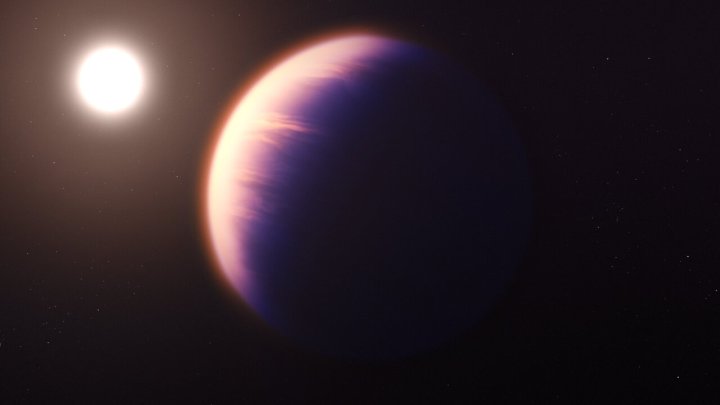

The planet in question, called WASP-39 b, is a gas giant orbiting a sun-like star and is located around 700 light-years away. Its mass if just a quarter of the mass of Jupiter, but its diameter is 1.3 times Jupiter’s, so it is not dense and is very puffy. As it orbits very close to its star, with a year there lasting just over four Earth days, it has very high surface temperatures and is a type of planet called a hot Jupiter.

The research team was able to see into WASP-39 b’s atmosphere using Webb’s NIRSpec instrument. This spectrometer splits light into different wavelengths to see which wavelengths have been absorbed — and that indicates the composition of the object. When looking at the light coming from the host star when the planet passed in front of it, the researchers could get data on its atmosphere using a method called transmission spectroscopy.

The results show a clear blocking of light between the 4.1 and 4.6-micron wavelengths, which indicates the presence of carbon dioxide. “As soon as the data appeared on my screen, the whopping carbon dioxide feature grabbed me,” said one of the researchers, Zafar Rustamkulov of Johns Hopkins University, in a statement. This is the first time that carbon dioxide has been identified in an exoplanet atmosphere. “It was a special moment, crossing an important threshold in exoplanet sciences.”

Learning about exoplanet atmospheres helps to understand how the planet evolved. And as well as helping scientists to learn about this particular planet, the results are an exciting demonstration of how James Webb can help us learn about other exoplanets in the future. “Seeing the data for the first time was like reading a poem in its entirety, when before we only had every third word,” said team member Laura Kreidberg of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy. “These first results are just the beginning; the Early Release Science data have shown that Webb performs beautifully, and smaller and cooler exoplanets (more like our own Earth) are within its reach.”

The research will be published in the journal Nature.