We are entering a new period of exoplanet astronomy, with a recent announcement that the James Webb Space Telescope has detected its first exoplanet. The promise of Webb is that it will be able to not only spot exoplanets but also study their atmospheres, which would mark a major step forward in exoplanet science.

Studying exoplanets is extremely challenging because they are generally far too far away and too small to be observed directly. Very occasionally, a telescope is able to directly image an exoplanet, but most of the time researchers have to infer that a planet is present by looking at the star around which it orbits. There are several methods for detecting planets based on their effects on a star, but one of the most commonly used is the transit method, in which a telescope observes a star and looks for a very small dip in brightness which happens when a planet passes between the star and us. This is the method Webb used to detect its first exoplanet, named LHS 475 b.

The big aim, though, is for Webb to detect exoplanet atmospheres. The researchers were able to gather some data on the newly detected planet’s atmosphere and to rule out some possibilities, but they aren’t yet able to determine the exact composition of its atmosphere. That’s because as difficult as it can be to detect an exoplanet, studying its atmosphere is even harder.

The way Webb does this is by using a method called transit spectroscopy. Like using the transit method to detect an exoplanet, studying its atmosphere also relies on the planet passing in front of its star (called a transit). When the planet is in front of the star, a small amount of light coming from the star will pass through the planet’s atmosphere. If scientists can hone in on that light and split it into different wavelengths, they can see which wavelengths are missing — indicating which wavelengths have been absorbed by something in the atmosphere. We know what chemicals absorb at which wavelengths, so this information can show what the atmosphere is composed of.

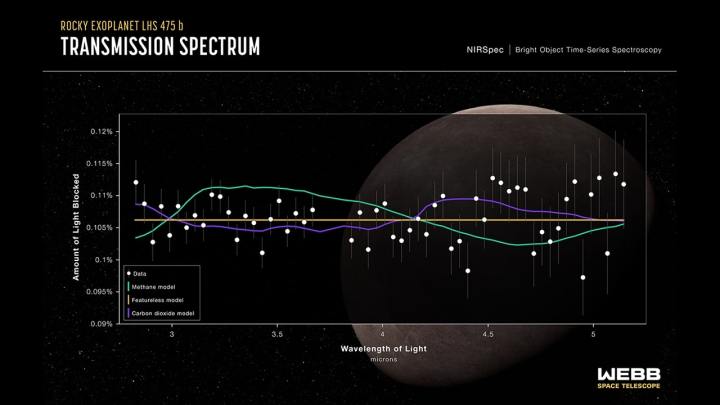

However, trying to piece together information from a transmission spectrum is complicated as the percentage of light being blocked is so low, at around 0.1% of the star’s brightness. And bear in mind, this is a star located 41 light-years away. If you look at the transmission spectrum of the recently detected planet, shown below, you can see the data points in white.

The colored lines are possible models of what the atmosphere could be like, and the researchers look for the line with the best fit. In this case, you can see that the methane atmosphere, shown in green, clearly isn’t correct, so that’s how the researchers know the planet doesn’t have a methane atmosphere. But it could have no atmosphere (shown in yellow, labeled as featureless) or a carbon dioxide atmosphere. There isn’t enough data to say definitively, though the researchers plan to make more observations with Webb later this year which should give them more data.

Even though we can’t be sure about the atmosphere of this exoplanet yet, this research shows how Webb should be able to analyze exoplanet atmospheres someday soon. “We’re at the forefront of studying small, rocky exoplanets,” said lead researcher Jacob Lustig-Yaeger of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in a statement. “We have barely begun scratching the surface of what their atmospheres might be like.”