If yesterday’s deep field image got you excited for the James Webb Space Telescope, there’s a veritable feast of space images on offer today. NASA has released four more images showing off the capabilities of the world’s most powerful space telescope and giving a taster of what science it will be able to perform in the future.

First up is a stunning image of the Carina Nebula, nicknamed the Cosmic Cliffs for its mountainous shapes. This cloud of dust and gas is a star-forming region that is lit up by bright young stars. These huge, hot young stars give off stellar winds which shape the gas into these stunning structures, and studying the region can help to learn about how common these young stars are and how they influence star formation around them. The nebula is located 7,600 light-years away and was captured using two of Webb’s cameras, NIRCam and MIRI.

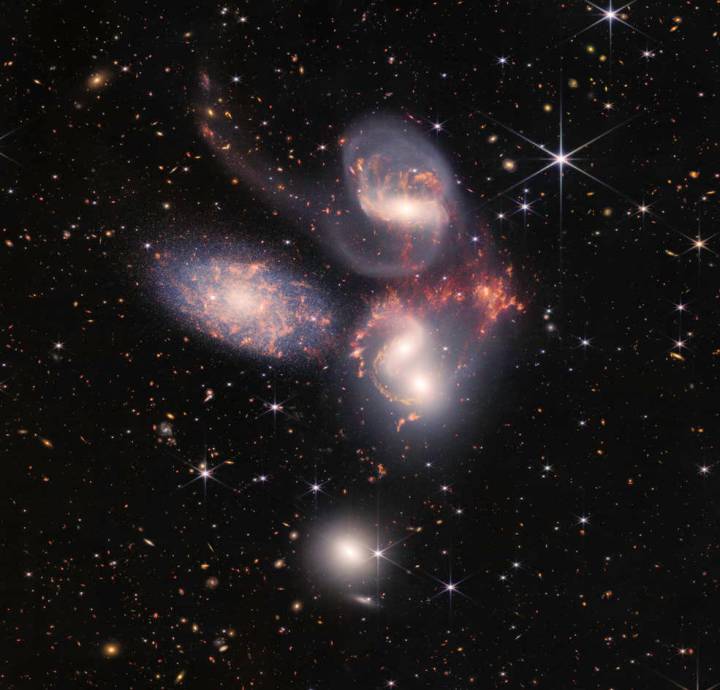

The second image is a quintet of galaxies locked into a cosmic dance. Four of the five members of the galaxy group Stephan’s Quintet are extremely close together and are in the process of merging, giving scientists information about how galaxies grow larger and evolve over time. This is Webb’s largest image so far, covering a huge area in an image of over 150 million pixels. The closest galaxy of the group is located 40 million light-years away, while the other four are much more distant at 290 million light-years away.

This striking structure is called the Southern Ring Nebula and is a type of nebula that is formed by a dying star throwing off layers of dust and gas. This dust and gas spreads out into space and forms a huge shell, which makes it hard to see the structure of the nebula in the visible light range. But in the infrared wavelength, where Webb operates, it is possible to peer inside the dusty shell and see the nebula beneath. This image shows how imaging the same structure in different wavelengths can bring out different features of an object, as the image on the left was taken in the near-infrared by Webb’s NIRCam, and the image on the right was taken in the mid-infrared by Webb’s MIRI instrument.

Finally, the last treat from Webb today is not an image but a spectrum, or an analysis of the light coming from a distant planet. Using spectroscopy, Webb was able to determine that water is present in the atmosphere of the superhot planet WASP-96 b. This gas giant orbits so close to its star that a year there lasts just three and a half Earth days, and it is estimated to have a surface temperature of over 1000°F. Before Webb, it was extremely difficult to analyze the atmospheres of exoplanets so the ability to detect gas molecules in an exoplanet atmosphere is a major step forward in planetary science.