Scientists convened in Germany in April for the seventh annual European Conference on Space Debris to discuss ways to address the millions of pieces of junk orbiting our planet. At the top of the list was concern that the problem is getting exponentially worse — in under a quarter century, the amount of space debris large enough to destroy a spacecraft more than doubled, according to experts.

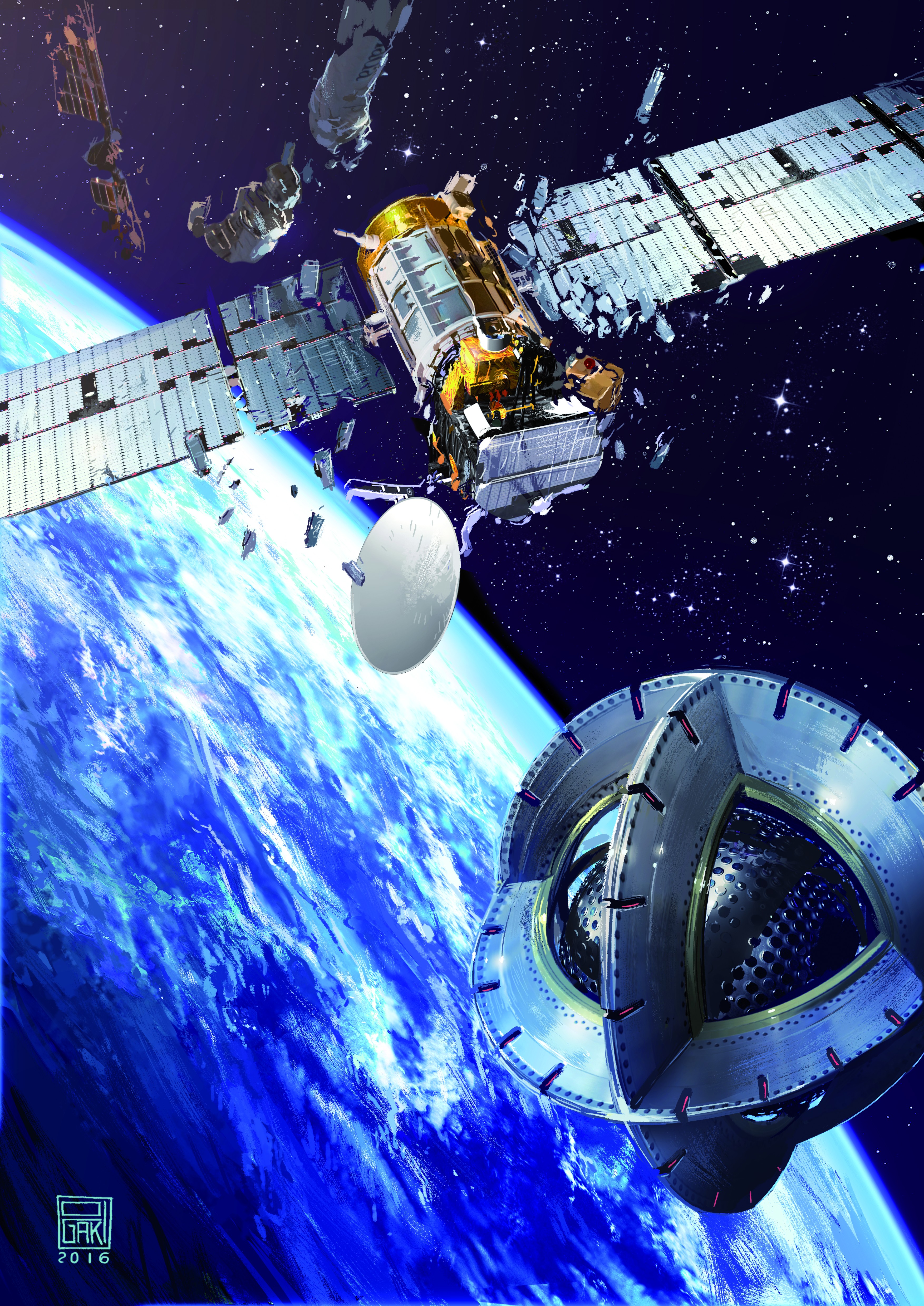

There are now more than 100 million pieces of space junk orbiting Earth, 29,000 of which are big enough to cause major damage. The cloud is made up of retired satellites, metal expelled from rockets, and abandoned equipment.

Equally worrying is the lack of a proven and reliable plan to clean up all this debris. A handful of proposals have been made — from the European Space Agency’s (ESA) plan to shoot large nets at derelict satellites to the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency’s (JAXA) comparatively simple plan to magnetically pull debris out of orbit using an electromagnetic cable.

Unfortunately, JAXA’s mission failed in February. “We believe the tether did not get released,” leading researcher Koichi Inoue told the Agence France-Presse. “It is certainly disappointing that we ended the mission without completing one of the main objectives.”

Nonetheless, ESA hasn’t abandoned the idea of using magnetic attraction and is now looking into this method for both debris removal and to keep swarms of satellites in close formation.

The new project is lead by researchers at the University of Toulouse in France.

“With a satellite you want to de-orbit, it’s much better if you can stay at a safe distance, without needing to come into direct contact and risking damage to both chaser and target satellites,” Emilien Fabacher, a researcher from Institut Supérieur de l’Aéronautique et de l’Espace, said in a statement. “So the idea I’m investigating is to apply magnetic forces either to attract or repel the target satellite, to shift its orbit or de-orbit it entirely.”

The chaser satellite’s magnetic field would be created by cooling superconducting wires to cryogenic temperatures.

As satellites are already equipped with electromagnets, the method wouldn’t require any additional changes to the derelict satellites. Fabacher’s chaser satellites would also be able to attract and position multiple satellites in a desired formation, according to Finn Ankersen, an ESA expert in rendezvous, docking, and formation flight.