When spacecraft launch to visit distant planets in the solar system, they rarely travel directly from Earth to their target. Because of the orbits of the planets and limitations on fuel, spacecraft often make use of other planets they pass by to get a gravity assist to help them on their way. And that means that spacecraft frequently perform flybys of planets that are not their main focus of study.

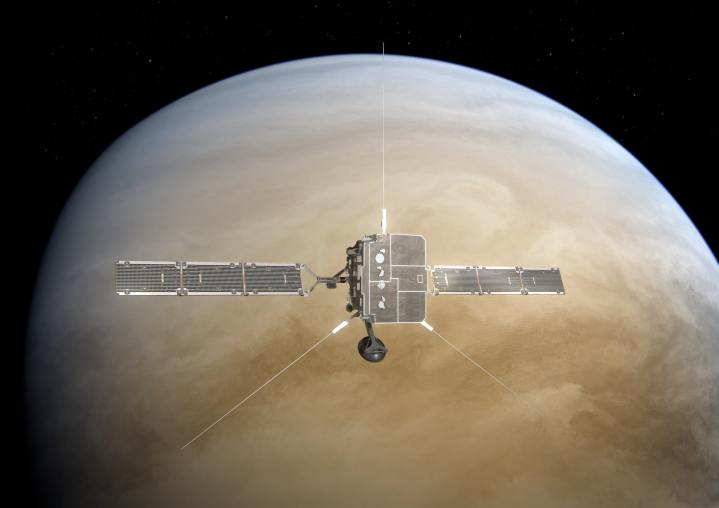

Researchers don’t waste any opportunity to learn about other planets though, so spacecraft often take as manyreadings as they can when passing by. For example, both the BepiColumbo spacecraft, on its way to study Mercury, and the Solar Orbiter spacecraft, designed to study the sun, have made recent flybys of Venus. Now, researchers are combining data from both of these missions to learn more about Venus and its magnetic field.

Both spacecraft happened to fly past Venus within a few days of each other in August 2021, allowing scientists to get a view of the planet from two different positions using eight different sensors. They were particularly interested in the planet’s magnetic field, as unlike Earth, it does not generate an intrinsic magnetic field, but the interaction of the solar wind and its atmosphere does produce what is called an induced magnetosphere.

The Solar Orbiter observed the solar winds approaching Venus, while BepiColombo observed the tail of the induced magnetic field. “These dual sets of observations are particularly valuable because the solar wind conditions experienced by Solar Orbiter were very stable. This meant that BepiColombo had a perfect view of the different regions within the magnetosheath and magnetosphere, undisturbed by fluctuations from solar activity,” said Moa Persson of the University of Tokyo in Kashiwa, Japan, lead author of a paper on the topic that was published in Nature, in a statement.

The researchers found that the magnetosphere is protecting the planet’s atmosphere from being eroded away by solar winds, which can help us understand more about conditions of habitability.

It also shows how valuable bonus science can be when data is collected from spacecraft passing by a planet by. “The important results of this study demonstrate how turning sensors on during planetary flybys and cruise phases can lead to unique science,” said co-author Nicolas Andre, the coordinator of the Europlanet SPIDER service at the Institut de Recherche en Astrophysique et Planétologie in Toulouse, France.