Last September, the astronomical community was shaken by research that indicated there could be signs of life on Venus. The researchers found indicators of a gas called phosphine in the Venusian atmosphere, which as far as we know is produced only by anaerobic (non-oxygen-reliant) bacteria.

Since then, scientists have debated back and forth about this finding and whether it was reliable. Now, a new study suggests that the gas which was detected was not phosphine but was in fact sulfur dioxide, a much more common gas with no special relation to life.

The new study by researchers at the University of Washington used a computer model of the atmospheric conditions of Venus to understand what could have given off the signal which was thought to be phosphine. They think there is a more prosaic explanation for the readings.

“Instead of phosphine in the clouds of Venus, the data are consistent with an alternative hypothesis: They were detecting sulfur dioxide,” said co-author Victoria Meadows, a UW professor of astronomy, in a statement. “Sulfur dioxide is the third-most-common chemical compound in Venus’ atmosphere, and it is not considered a sign of life.”

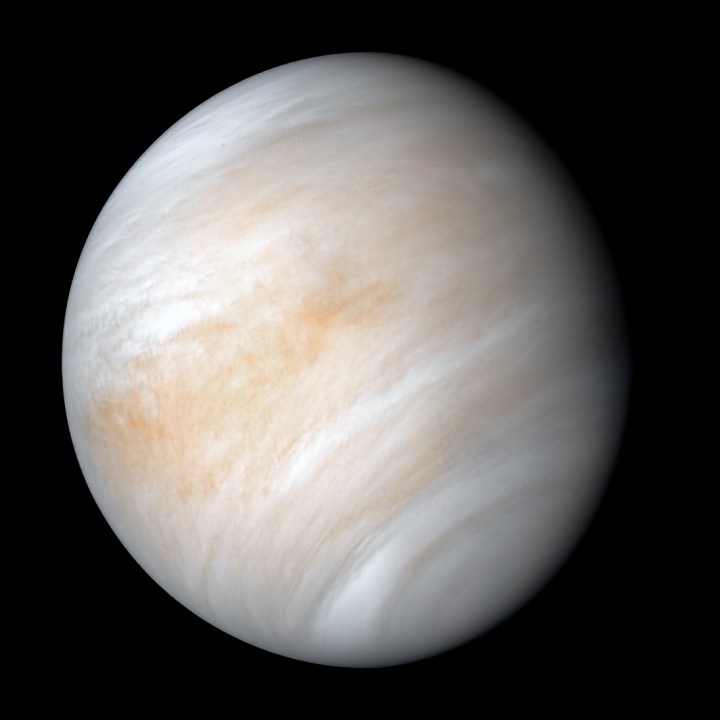

The team also says that the signal coming from sulfur dioxide is more consistent with what we know about the environment of Venus than phosphine would be. The surface of Venus is hidden beneath dense clouds of sulfuric acid, with an atmosphere that is whipped around by high wind speeds.

The difficulty in working out whether there really is phosphine in the atmosphere comes from the methods used to examine the planet. As we can’t collect a sample of the Venusian atmosphere directly, researchers use radio telescopes to look at the planet. These radio telescopes show absorption in the radio waves at a particular wavelength — 266.94 gigahertz — which is around the frequency absorbed by both phosphine and sulfur dioxide. It’s difficult to tell which of the chemicals is causing the absorption, which is why there have been debates and a number of studies since trying to pick apart this puzzle.

This new finding doesn’t definitely disprove the hypothesis of phosphine on Venus, but it does make it seem less likely. We’ll have to wait for more debate and more data for a final answer on our mysterious planetary neighbor and the possibility of life there.