The James Webb Space Telescope has directly imaged an exoplanet for the first time. This is exciting because it is very rare for exoplanets to be directly imaged, as usually, their existence has to be inferred from other data. By taking an image of a planet outside our solar system, Webb demonstrates how we’ll be able to gather more information than ever before about distant worlds.

There are over 5,000 known exoplanets, but the vast majority of these have been detected using techniques like the transit method, in which the light from a host star dips slightly when a planet passes in front of it, or radial velocity, in which a star is slightly tugged around by the gravity of a planet. In these methods, the existence of a planet is inferred because of the effect that can be observed on a star, so the planet itself isn’t directly observed. In rare cases, however, an exoplanet can be observed directly, particularly if it is a large planet located relatively nearby.

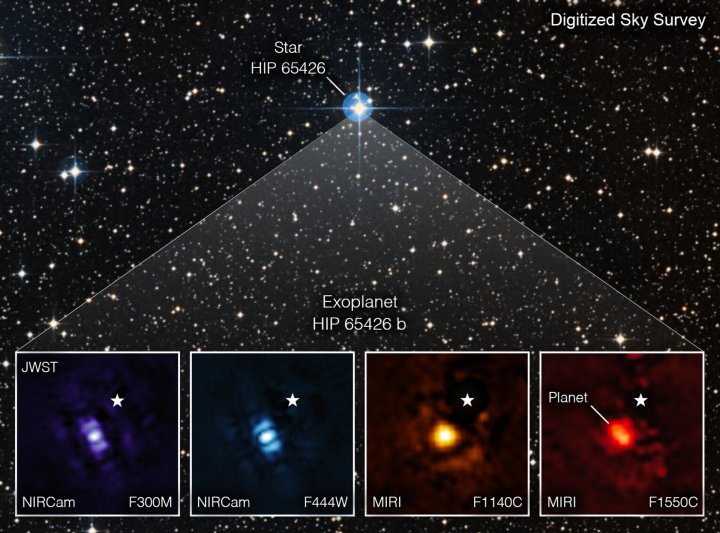

Webb made one such direct observation of the exoplanet HIP 65426 b, and was able to capture an image of the planet using four different filters. Each of these filters corresponds to a different wavelength of light, capturing different features of the planet and its environment. The planet is a big one at between six and 12 times the mass of Jupiter, and it is a relative youngster at just 15 to 20 million years old.

“This is a transformative moment, not only for Webb but also for astronomy generally,” said leader of the observations Sasha Hinkley in a statement.

To observe the planet, the researchers needed to block out the light coming from the planet’s host star. As the star is so much brighter than the planet, this light has to be blocked to make it possible to see the planet. This is done with an instrument called a coronagraph, which is a mask that blocks light from a bright source.

“It was really impressive how well the Webb coronagraphs worked to suppress the light of the host star,” Hinkley said.

“Obtaining this image felt like digging for space treasure,” said another of the researchers, Aarynn Carter. “At first all I could see was light from the star, but with careful image processing I was able to remove that light and uncover the planet.”

This finding demonstrates some of Webb’s abilities when it comes to finding and investigating exoplanets. “I think what’s most exciting is that we’ve only just begun,” Carter said. “There are many more images of exoplanets to come that will shape our overall understanding of their physics, chemistry, and formation. We may even discover previously unknown planets, too.”