“You cannot go to the grocery store on the moon,” said Didier Toubia, speaking with great solemnity, as if he was addressing one of humanity’s most fundamental problems. Which, in a very real way, he is. “One of the main problems for the human species going really deep into space is the lack of food,” he told Digital Trends. “When we’re talking about a deep space operation like a spacecraft that is up there for five years, how do you feed the people [on board for that length of time] without any access to local food?”

When we picture long-haul space travel, the idea that a potential cause of failure could be something as simple as a lack of basic food is kind of mind-boggling. But this is exactly the challenge faced by pioneers setting out to explore new frontiers throughout human history. The assumption that food is in ready, unlimited supply is a sign of just how luxurious modern life is for many people.

“The steaks, quite literally, could not be higher.”

However, whether it’s the large crew of a galleon sailing across the ocean during the Age of Exploration or a future spacecraft carrying colonists to Mars during the Age of, well, Space Exploration, this ready availability of foodstuffs has not always been — and won’t always be — guaranteed.

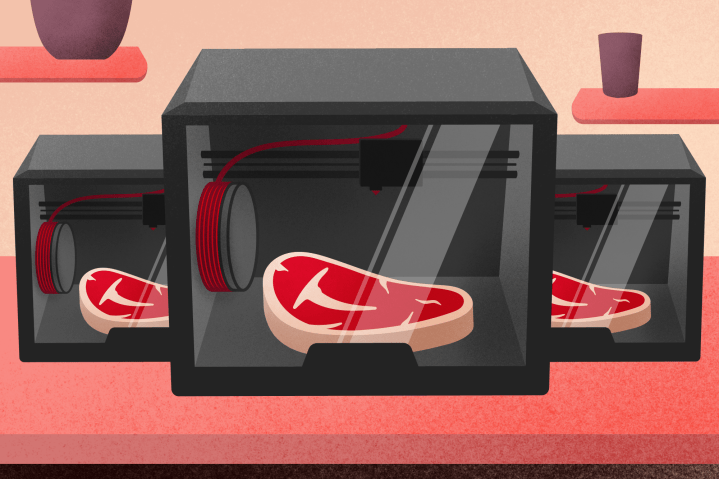

The difference between the two scenarios? If Toubia — and the venture capitalists backing him to the tune of $14.4 million to date — is correct, crew members during the Age of Space Exploration will have the ability to 3D print steaks on demand.

When humans go multiplanetary

Toubia, a biologist and “food engineer” by training, is the co-founder and CEO of an Israeli cultivated meat startup called Aleph Farms, one of an expanding number of companies working to create an alternative to breeding and slaughtering cattle by growing high-quality meat from animal cells. One of the key differentiators is that, along with a plan to grow meat for people on Earth, Toubia also has his eye on the stars. The steaks, quite literally, could not be higher.

“We believe that when the human species becomes multiplanetary, we will need to [follow to] make sure that we are able to provide a good food experience with nutritious meat anytime, anywhere,” he said.

Toubia’s dream of growing meat in space might sound like it’s decades away, but the timeline could be much, much closer. “I believe we’ll be able to deliver the first pieces of meat within four to five years from now,” he said.

In the second half of last year, Aleph Farms made history as the first company to successfully grow meat on the International Space Station, some 248 miles from the natural resources the company’s foodstuff is based on. Bovine cells that had been extracted on Earth were grown into small-scale muscle tissue with the aid of a 3D bioprinter. The demonstration — which resulted in a very small quantity of meat produced — was carried out September 26 on the space station’s Russian segment in microgravity conditions.

“Meat would be a welcome luxury for many astronauts; not just for nutrition, but also as a luxury that could provide a psychological boost to humans far, far away from their home planet.”

For obvious reasons, Toubia and his team were not able to carry out the demo in person. Instead, it was one of the many experiments assigned to astronauts on the ISS. Toubia could only bite his knuckles back on Earth and hope for the best.

“It’s quite stressful, you know,” he said. “It was a one-shot [deal] because the crew time in space is so critical. They have very limited time to perform an experiment, and there’s no ability to fix anything. We wanted to be very, very well-prepared before we shipped up the test. We had been working intensively on it for one year. We were hopeful that nothing would go wrong. In the end, it went very smoothly.”

Taking a bite out of the meat industry

At present, astronauts on the ISS receive the food they need on regular resupply missions. This isn’t just vital food but also, on occasion, treats. For example, in February of this year, a resupply mission contained an assortment of fresh fruits and vegetables, chocolate, cheddar and manchego cheeses, and a range of candy including Skittles, Hot Tamales, and Mike and Ikes. But as Toubia points out, once you go deeper into space, this becomes an impossibility. Particularly if you’re not staying in orbit but actively rocketing away from the Earth.

A certain amount of food can be taken on board, the way an airplane carries food for its passengers. However, after a certain point, it’s essential to start creating new food as well. Efforts are already underway (as depicted in the movie and book The Martian) to explore growing vegetables in space. But meat would be a welcome luxury for many astronauts: not just for nutrition, but also as a luxury that could provide a psychological boost to humans far, far away from their home planet.

“When we eat meat, it’s not just to fuel the body,” Toubia said. “We connect to the meat we eat on an emotional, social, and historical — sometimes even religious — channel. For meat to be produced [like this] and be successful, it has to be able to create the whole experience.”

Aleph Farms’ initial livestock or, err, “cellstock” is a beefsteak. But Toubia said that the company is also “working on adding two additional species” in the form of lamb and pork. Chicken may follow at some point, he said, although no plans are currently afoot.

Toubia and his team are on a bold mission, one that could one day prove transformative. In the meantime, though, Aleph is focusing on producing meat closer to home. He said a pilot market launch will take place during the second half of 2022. The meat market on this planet alone is worth some $1.2 trillion a year. Conquering Earth will be Aleph Farms’ focus at first: Showing that it can launch a product, scale up production facilities, and build a global brand.

After that? Toubia’s ambitions aren’t limited to anything as prosaic as global market domination.