In a 2013 essay, Gawker writer Hamilton Nolan declared what others had been saying for years: “the concept of ‘selling out’ no longer exists.” He was talking, of course, about music – the segment of human creation long encumbered by the idea that corporate-backed success kills that nebulous quality, authenticity. He was also, of course, right – at least when it comes to musicians.

As the news that Facebook is buying Oculus VR, maker of the Rift virtual reality headset, shows, however, “selling out” is not dead at all. It has simply sunk its teeth into a new fragment of creation – a world that I believe has, as music once did, come to profoundly define who we are as individuals – the world of consumer technology.

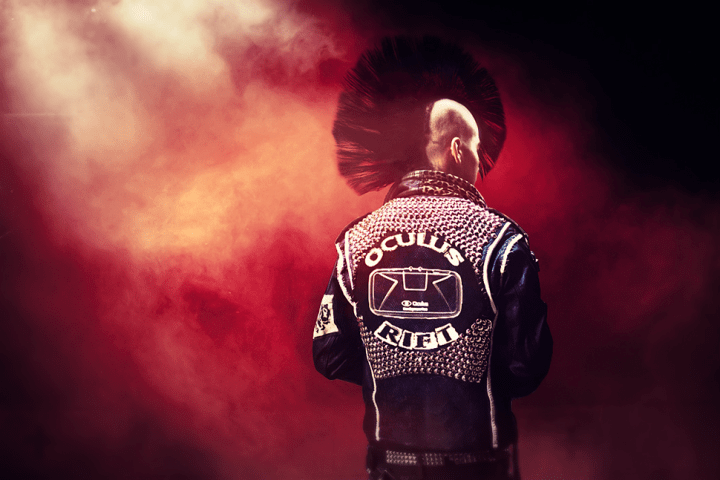

“I guess you might as well go full-evil when selling out.”

Fueling the “sellout” fire is the fact that, like indie bands, Oculus owes its early success to its fans, 9,522 of which collectively pledged more than $2.4 million to the company’s 2012 Kickstarter campaign. Like tune-crazed teenagers who spend their last dollars to see their favorite local band’s midnight set, these earliest of early adopters trudged into the dark and grungy club of Kickstarter to help make Oculus a reality. Now that Oculus has $2 billion in cash and Facebook stock, many feel left behind.

Thing is, the early fans are probably right – those who, to put it in hipster terms, ‘knew about Oculus before it was acquired’ are likely being left behind right along with Oculus’ indie spirit. Once devoted to gamers, hackers, makers, and indie developers, the Oculus Rift has fallen into the mainstream realm of “sharing” and “social experiences” – Facebook’s realm.

And what a dark realm that is. Facebook is not seen simply a soulless corporation – it is a malevolent beast. It is not just uncool; it is bad for society. For this reason, Minecraft creator Markus “Notch” Persson immediately responded to the Oculus-Facebook news by cancelling the port of his popular game to Oculus. “We were in talks about maybe bringing a version of Minecraft to Oculus,” he wrote on Twitter. “I just cancelled that deal. Facebook creeps me out.”

In a futile attempt to quell the critics, Oculus VR co-founder Palmer Lucky took to Reddit’s Oculus community to assure fans that nothing will change for the worse, that “we will not let you down.” His vows splattered on deaf ears.

“I feel like I’ve just been spit on,” responded one redditor, who claims to have contributed to the Oculus Kickstarter. “Somehow this feels like the betrayal of the community that made the Rift possible in the first place,” said another. Statements of pain and betrayal caused by this business deal go on and on and on.

What Lucky and anyone else who claims that the Facebook acquisition is a good thing – that it will provide Oculus with the resources to develop bigger, better, and faster – fails to grasp is our deeply personal connection to the gadgets we hold dear. State of the art is our new art. And it makes us angry when we think wealthy impostors have tainted it.

State of the art is our new art. And it makes us angry when we think wealthy impostors have tainted it.

We live in the age of fanboys and fangirls, of Mac vs. PC, iOS vs. Android. Which devices we use, which companies we support through our purchases, define who we are – they tell the story of our identity. They are signals of our ethics and aesthetics.

Indeed, even music is seen more as a product than an art – that elusive thing that exists outside the grip of money’s power – which may explain why “selling out” is now viewed as the savior of indie bands, not their executioner. While the music world has succumbed to mercy of advertising dollars, the new Kickstarted world of independent technology makers still seems above such a subservient position. The fact that Facebook and Oculus are the companies to prove that it’s not simply made that revelation all that more clear, and all that more painful.