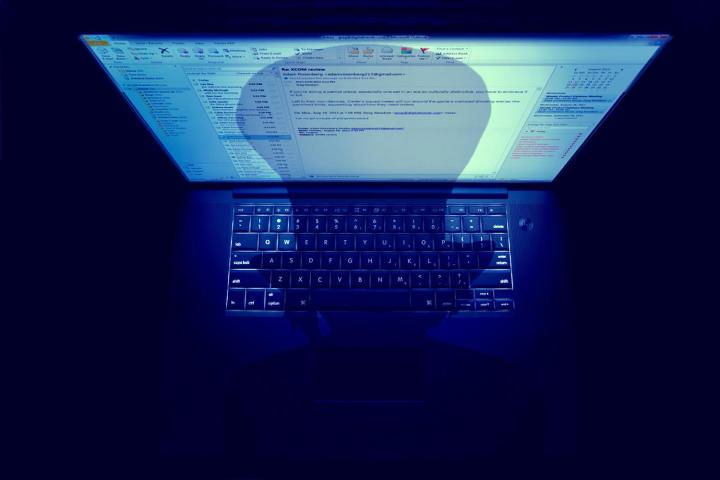

When Edward Snowden’s NSA leaks first hit a couple of months ago, it didn’t occur to me for one moment that news of widespread government surveillance might change anything. If a number of recent factors are any indication of the direction public opinion is headed, however, it seems as though change is exactly what lies ahead.

The first factor guiding my blasé reaction to the NSA news was a pessimist’s sense of inevitability. Of course the NSA is spying on us. Of course they are collecting all our phone records. Of course they scrape massive swaths of the Internet! Sure, maybe we didn’t have proof in the past – but the Washington Post and Guardian scoops only served as vindication for this worldview, not a wakeup call. And based on the reactions I gathered online and off, most other people felt similarly.

To this day, it is difficult for me to imagine an America that values anything more than safety.

The second factor came from my experience reporting and opining on privacy issues. To be blunt: Most people really didn’t seem to care about privacy as an inherently valuable part of life. Yes, an expectable uptick in privacy concerns would occur anytime Facebook changed one of its 8 billion account settings. But tell people that using Facebook at all is a self-imposed violation of privacy, and the only applause you’d receive was from the two guys who always sit in the back row wearing tin-foil hats.

Finally, our collective valuation of privacy – something we willingly cut to zero constantly on the Web, in exchange for free services – paled in comparison to our fear of terrorism, which is ostensibly the entire reason for the NSA’s surveillance activities. My adult life began in New York City just a few months before some assholes flew planes into the World Trade Center, and we’ve been at war for the same reason ever since. I am now 30 years old. And to this day, it is difficult for me to imagine an America that values anything more than safety; privacy, on the other hand, barely seems to make it into the top 20.

Empirical evidence of society’s “meh” attitude toward privacy arrived just days after the first Snowden leaks hit the news. A Washington Post-Pew Center poll published on June 10 showed that “56 percent of Americans consider the NSA’s accessing of telephone call records through secret court orders ‘acceptable.'” And 45 percent of respondents said the NSA “should be able to go further than it is,” assuming that more spying meant less terrorism.

What a difference a few months of non-stop coverage makes. Since that June 10 poll, the numbers have shifted firmly against the NSA. An Economist-YouGov poll shows that 59 percent of Americans now disapprove of NSA surveillance, and only 17 percent believe what agency officials are saying about its spying activities to the public. A recent Fox News poll (pdf) came to a similar conclusion, with a full 63 percent of respondents denouncing NSA surveillance. And even the latest Pew Research poll, which once put 56 percent in favor of the NSA’s activities, now finds that exact percentage believes the courts fail to provide adequate oversight, while 70 percent believe the NSA is using its spying powers for purposes other than preventing terrorism – a shift doubtlessly caused by the fact that it is.

More telling, this turn in opinion is translating into changes in behavior. According to online analytics firm Annalect, the number of people who adjusted their browser’s privacy settings due to news about the NSA jumped 12 percent since the first quarter of 2013. The number of people who changed their mobile tracking settings jumped 7 percent, according to Annalect.

Furthermore, 27 percent of those who previously identified as “not-concerned” Internet users changed their privacy settings, as did 37 percent of “concerned” users. While those numbers might not seem overwhelming, they are apparently high enough for the online advertising industry, which relies upon increasingly blocked user-tracking browser cookies to operate, to sound the alarm bells.

The number of people who adjusted their browser’s privacy settings due to news about the NSA jumped 12 percent since the first quarter of 2013.

On top of all this, we now have a real-life anecdote of government abuse to exemplify all our concerns about government overreach. On Sunday, British authorities detained Guardian journalist Glenn Greenwald’s partner, Brazil native David Miranda, at Heathrow airport for questioning, and cited the U.K.’s Terrorism Act to do so. Miranda was held for 8 hours and 55 minutes without access to a lawyer – just shy of the 9-hour time limit allowed under the law, when no arrest is made. Before letting him go, authorities confiscated his camera, laptop, USB drives, smartphone, DVDs, and game console, presumably in an attempt to obtain the remaining Snowden documents that Greenwald has not yet released to the public.

For blogger Andrew Sullivan, who has intelligently defended the NSA’s efforts as likely necessary in the ongoing gambit to prevent terrorism on a global scale, Miranda’s detention effectively broke the camel’s back.

“Britain is now a police state when it comes to journalists, just like Russia is,” writes Sullivan.

“In this respect, I can say this to [British Prime Minister] David Cameron. Thank you for clearing the air on these matters of surveillance. You have now demonstrated beyond any reasonable doubt that these anti-terror provisions are capable of rank abuse. Unless some other facts emerge, there is really no difference in kind between you and Vladimir Putin.”

In other words, the questioning of Miranda for reasons that appear to start and stop at intimidation of the press, is the first real consequence Sullivan has seen to support the view of staunch privacy advocates who warn about what the NSA and other government agencies are doing to our privacy and civil liberties.

As much as the public’s perspective on digital privacy has shifted since Snowden’s first revelations, I don’t see the Miranda incident doing much to sway those who haven’t yet been swayed. For that, unfortunately, I fear we need to see evidence of consequences of NSA spying suffered by someone other than the partner of a contentious celebrity journalist. We need to see this surveillance affect someone like you, your mother, your sister. And so far, those consequences remain the hypothetical brainchildren of privacy cranks like myself.

This not to say I want any innocent person to suffer any consequences. I am simply saying that that may be the only thing to push this debate all the way to the other edge. Then again, I have been fooled before.